-

[금융/시황/전략] (Bloomberg) Brace for a Trading Bounce or Recession — or Both2023.10.30 PM 09:03

블룸버그 기사 요약

A Receding Recession?

경제 데이터와 주가의 불일치가 극단적인 수준

→ 美 3분기 GDP 성장률 4.9% vs S&P 500 조정장 진입 (고점 대비 -10%)

관건은 향후 경기 침체 발생 여부

국채 금리는 오르고, 주가는 하락하는 이유

→ 올해 초 지역 은행 위기가 닥쳤지만, 예상했던 경기 침체는 발생하지 않았기 때문

→ 경제 지표가 계속 긍정적으로 나오자, 국채 수익률 곡선이 정상화되고 있음

주식 강세장은 대부분 약세장에서 시작했음

따라서, 앞으로 경기 침체가 발생한다면, 주가는 계속 약세를 보일 것

Those Stocks

올해 S&P 500 상승은 대부분 매그니피센트 7 종목에 의한 것

동일 가중 S&P 500 지수는 작년 10월 저점 아래로 하락

심지어 MSCI 신흥국 지수, 미국을 제외한 전 세계 지수를 언더퍼폼

월스트리트 애널리스트들의 올해 연말 S&P 500 지수 전망치는 5,082

반면 지난 금요일 기준 S&P 500 지수는 3839

월가의 전망치가 너무 높거나, 시장이 지나치게 비관적이라는 의미

결국 S&P 500 지수는 둘 중 어느 한 쪽 방향으로 움직일 것

경제 상황에 매우 민감한 운송 종목은 급락하고 있음

이런 상황에서, 우리는 단기 반등 or 경기침체, 또는 둘 모두에 대비해야 함

Inflation and the Fed

(연준이 선호하는) 9월 PCE 물가 데이터는 하락 추세를 유지했지만, 여전히 연준의 목표치 대비 높은 수준

→ 근원 (에너지, 식품 제외) 및 절삭 평균 (극단값을 제외) ↓

이런 상황에서, 파월 의장이 완화적으로 돌아설 가능성은 낮음

위험 자산이 상승하면, 연준의 인플레 목표치 2%를 달성하는 것이 아려워지기 때문

반면, 최근 국채 시장의 혼란으로 인해, 연준이 매파적으로 나오기도 어려울 것

따라서, 시장의 초점은 수요일에 발표될 재무부 국채 발행 계획에 쏠릴 것

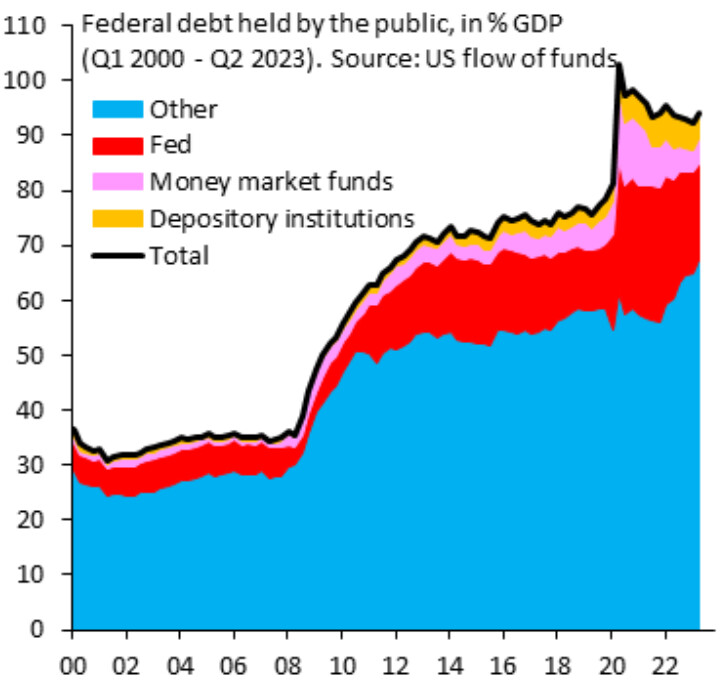

국채 발행이 급증했지만, 연준은 국채 보유량을 줄이고 있기 때문에, 그 물량을 받아줄 투자자가 필요함

재정 적자 심화와 그로 인한 국채 발행 증가로 인해, 시장은 단기 경제 전망에 더욱 민감하게 반응할 것

→ 경기 침체 발생 시, 세금 수입 감소/복지 지출증가, 따라서 국채 발행은 더 늘어나기 때문

The Bottom Line (기업 실적)

매그니피센트 7의 3분기 실적 (전년 대비)

→ 이익 +33%, 매출 +11%

나머지 S&P 500 기업 (전년 대비)

→ 이익 -8.6%, 매출 0%

이익이 예상보다 높았떤 기업이 더 많고, 주당순이익은 역대 최고 수준

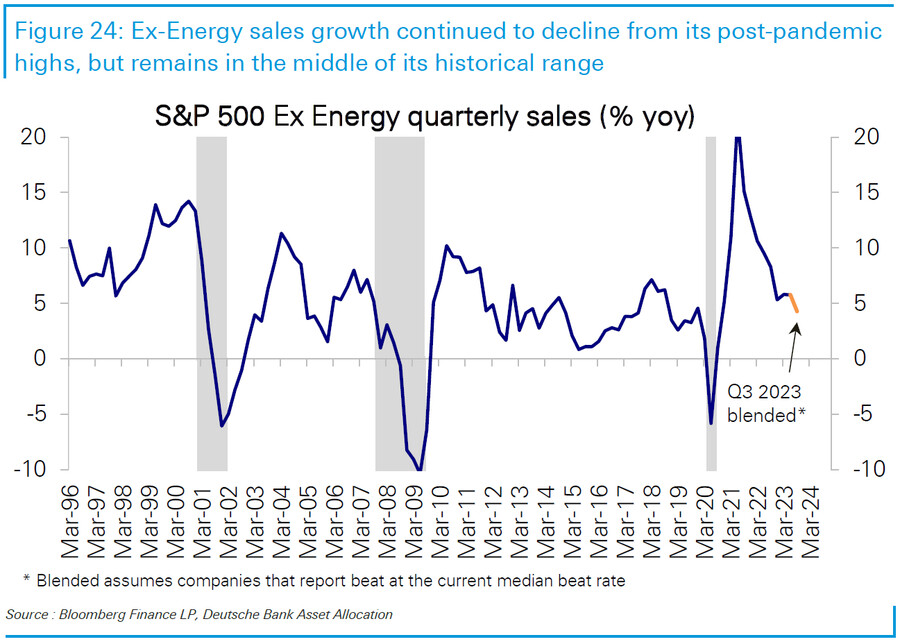

반면, 매출 성장률은 하락 추세이며, 예상치를 하회하는 경우가 많았음 (변동성이 큰 에너지 제외)

매출 성장률은 역사적 평균치를 상회하지만, 기업은 경기 활황의 수혜를 충분히 누리지 못하고 있음

마진은 팬데믹 이전 수준을 회복

대량 해고 없이 마진을 올린 것은 인상적

하지만, 이는 기업들이 투자를 줄였다는 뜻이므로 경제 성장에는 부정적

당장 경기 침체가 오진 않겠지만, 기업 임원들이 제시하는 향후 실적 전망은 부정적

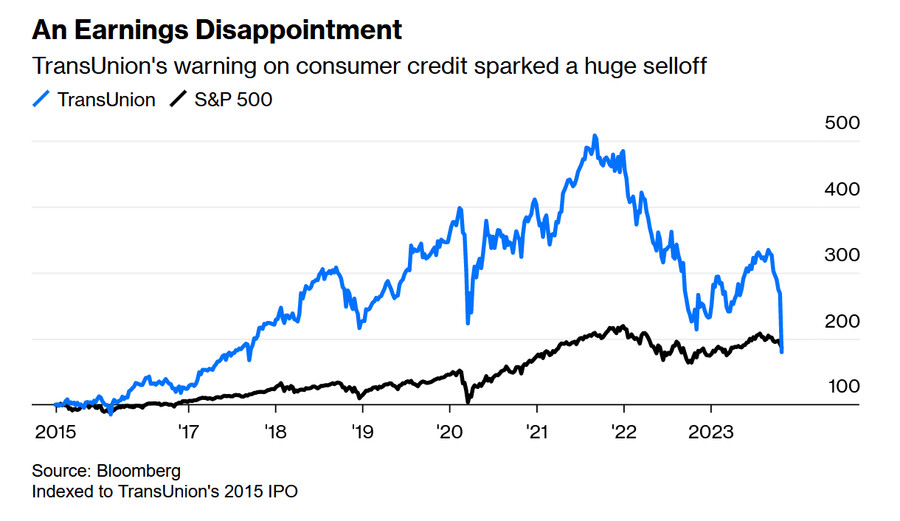

메타, 트랜스 유니온 (개인 신용 평가 기업) : 부정적 가이던스를 발표하자 주가 급락

소비자 신용에 금이 가고 있음 (특히 저신용자들)

미국 초콜릿 생산 업체 허쉬(HSY)는 어닝 서프라이즈를 기록했지만, 향후 가이던스는 보수적

소비자들은 임의 소비를 줄이고 있으며, 할인 판매를 선호했으며, 더 작은 사이즈를 구입

놀라울 정도로 강한 경제 데이터는 채권 시장의 약세를 불렀지만, 이런 호경기가 오래 갈 수 없을 것이라는 증거가 쌓이고 있음

==========================================

Seldom do the stock market and the economy diverge quite this much, but they’re also more tightly linked than usual right now.

2023년 10월 30일 오후 1:37 GMT+9

By John Authers

John Authers is a senior editor for markets and Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A former chief markets commentator at the Financial Times, he is author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets.”

The current disjunction between the stock market and economy seems extreme.

Photographer: Stephanie Keith/Bloomberg

A Receding Recession?

The economy and the stock market are not the same thing, at all. In the short run, there’s no particular reason to expect them to move in the same direction, even though in the long run they both tend to grow, with occasional interruptions. At present, the disjunction seems extreme: Last month saw both a blowout number for third-quarter gross domestic product growth, of 4.9%, and a selloff in the stock market that brought the S&P 500 more than 10% below its recent peak — satisfying a popular definition of a “correction.”

However, at present the two are more tightly linked than usual. The big question for stocks is whether the bear market is really over (with US prices still well above their lows from last year). If it is, you should take the opportunity to buy, and if the bear market merely hibernated and never ended, then you should take the chance to sell. And the answer to that lies in a question about the economy: Is there going to be a recession in the US?

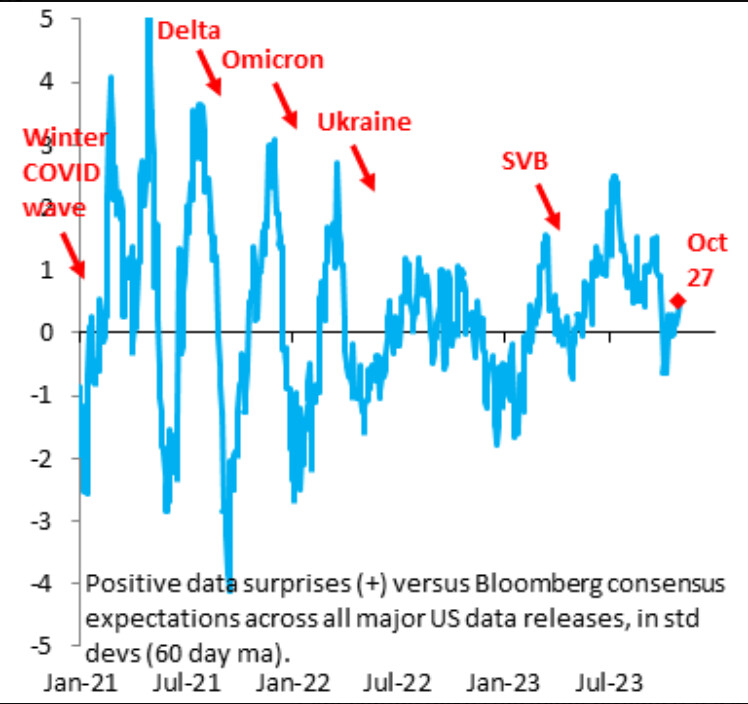

This is where it gets interesting. Bond yields have surged upward, and stocks have sold off, in large part because the assumption that the regional bank collapses earlier this year would drive a recession has proved incorrect. They might well yet contribute to an economic downturn, but the strength of the latest GDP numbers show that something more will be needed. According to Robin Brooks of the Institute of International Finance, the best explanation for rising yields is “that the US did NOT go into recession after SVB blew up. That’s meant that — relative to bearish consensus — data kept surprising positively, which forced the yield curve to uninvert.” He illustrated this with Bloomberg data in this chart:

Markets have capitulated on their belief in an imminent recession under the weight of a welter of positive data. That’s been bad news for bonds, evidently. The implications for stocks are more nuanced, but in general there are precious few examples from history of a bull market starting other than when there is already a recession. That implies we should expect the bear market to continue if a recession is really ahead.

Those Stocks

The problem, as we’ve documented in Points of Return, is to squint and work out what’s happening if you exclude the influence of the “Magnificent Seven” stocks — Apple Inc. , Amazon.com Inc., Alphabet Inc., Meta Platforms Inc., Microsoft Corp., Nvidia Corp. and Tesla Inc. — which dominate large-cap indexes. The S&P 500 is still up for the year, and only just 10% off its peak — but if we simply take an equal-weighted version of the S&P, in which each company accounts for only 0.2%, then we find it’s down for the year, and slightly lagging the popular benchmarks for the world outside the US, and for emerging markets. The Magnificent Seven seem to be inhabiting a different economy:

Nicholas Colas of DataTrek Research points out that Friday’s closing level of the S&P 500, of 3,839.5, is drastically at variance with the current estimates from Wall Street analysts, many of whom moved up their year-end targets for the benchmark during the summer when the market was rallying. He explains as follows:

"One simple metric we’ve used over the years to know when fundamentals have diverged materially from market sentiment is the difference between analysts’ aggregate S&P 500 price targets and current prices. When the Street thinks the S&P should be 20% or higher than where it is actually trading, something has gone wrong. According to FactSet, analysts’ current price targets on the index bubble up to 5,082. We are 23 percent away from that number today. Either the Street’s estimates and price targets are way too high, or markets are excessively bearish. We’ve seen things break either way (stocks higher or lower three months later) whenever this happens."

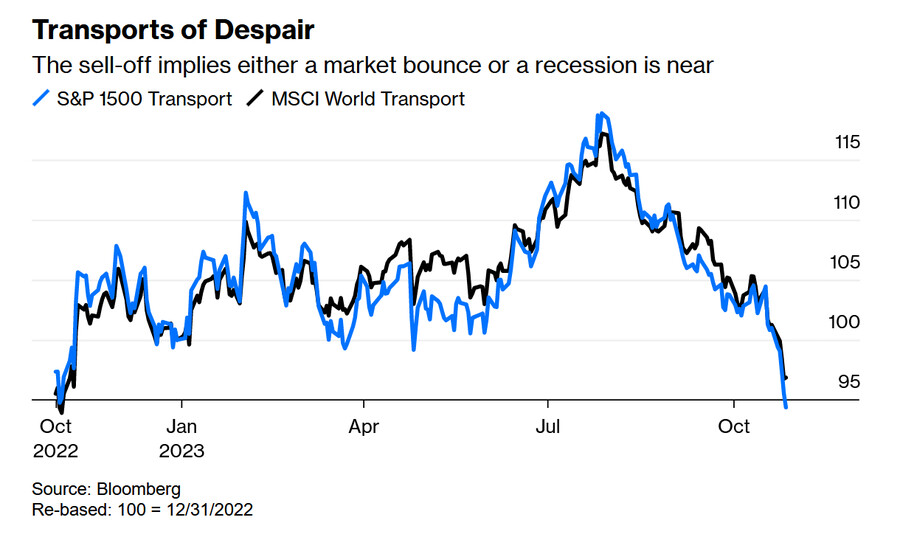

For indications that the market is indeed bearish, and possibly excessively so, the highly economically sensitive transport stocks are in a tailspin:

On the face of it, after performance like this, we should brace for a trading bounce or a recession — or both.

Inflation and the Fed

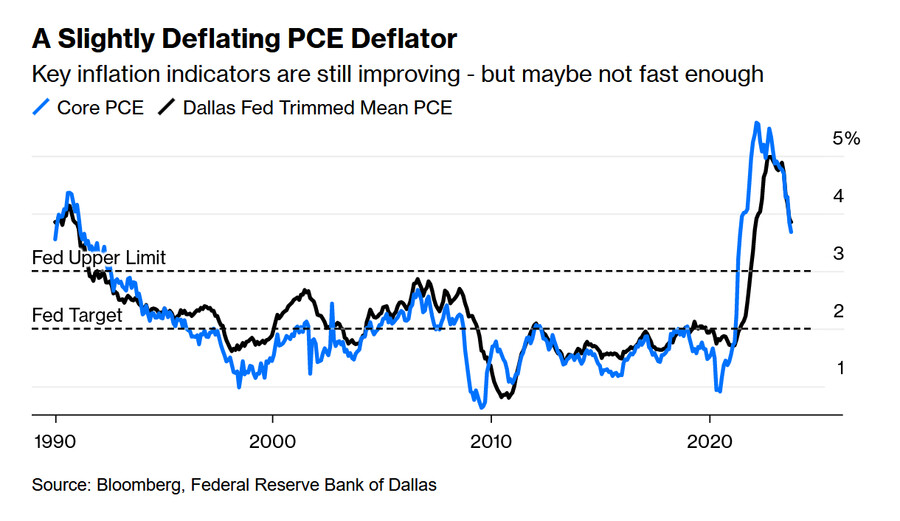

We hear from Jerome Powell and the Federal Open Market Committee this week. Barring a major surprise, there will be no rise in interest rates, meaning that the central bank will have been on “pause” since July. It’s hard to imagine that Powell will renounce the option of hiking again, however, because inflation is not under sufficient control for him to do so.

Last week saw the release of Personal Consumption Expenditure deflator data for September, the Fed’s favored measure of inflation. If we look at two popular measures of underlying or core inflation — a straightforward “core” that excludes food and fuel, and a “trimmed mean” produced by the Dallas Fed that excludes the outliers and averages the rest — we find that both are decreasing, but remain above the Fed’s comfort zone. Fed governors tend to be judged by their record in containing inflation, and that will make them hugely reluctant to claim victory just yet:

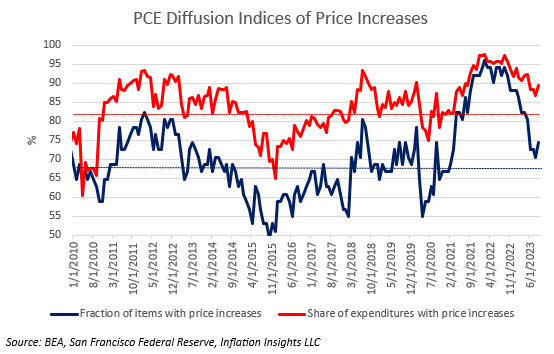

Looking into the entrails of the PCE data, Omair Sharif of Inflation Insights LLC also demonstrates that the distribution of products and services that are still seeing the highest inflation is likely to make consumers unhappy. The chart gives the proportion of PCE components showing an increase (in blue, and more-or-less back to normal), and the proportion of the expenditures that consumers are currently making where prices are rising, which is right at the top of the historical range:

Thus, consumer attitudes might not improve as much as might otherwise be expected. That would generally imply a greater risk ahead of a loss of consumer confidence, which could induce a recession — although that certainly hasn’t happened yet.

These inflation numbers effectively make it impossible for Powell to do anything to try to talk yields down, even though higher interest rates mean a rising risk of a big credit event. Until that credit event actually happens, he has to continue on his current course. Komal Sri-Kumar, writing in his Srikonomics newsletter, explains the dilemma for Powell as follows:

"There is little expectation that the volatility in bonds will cause him to suggest an explicit reversal of policy — an end to Quantitative Tightening and a move toward lower interest rates. A policy reversal would cause a rally in risk assets and, in the process, making it even more difficult to bring inflation down to 2%. On the other hand, the recent turbulence in bonds must have sufficiently frightened the Fed into not providing a tough message. I do not expect benevolent Uncle Jay to say “Uncle” on Wednesday. He needs a credit event to push him to that stance."

So limited is Powell’s ability to change direction at this point that there’s every chance his thunder will be stolen Wednesday by the Treasury Department’s announcement of its borrowing needs for the quarter. The potential for that number to move the bond market looks very much greater than anything the Fed is likely to say. After all, as this IIF chart demonstrates, the market has been asked to swallow a lot of debt, and if the Fed keeps its word about stepping back (QT), someone is going to have to buy more:

The scale of the deficit and lending needs ensures that markets grow ever more geared to short-term moves in the economy. A recession would mean lower tax receipts and higher welfare payments; in current circumstances, Uncle Sam would probably have to pay up to finance that.

The Bottom Line

Yet again, corporate earnings are subject to a magnificent distortion. All the Magnificent Seven except Apple and Nvidia have reported so far, and none has seen a rise in share prices on the back of it. Sarah McCarthy of Alliance Bernstein points out how lopsided the market has become: “The seven mega caps are expected to grow earnings in the third quarter collectively by +33% year-over year on 11% higher revenues versus the rest of the S&P, which is expected to have a decline of -8.6% in earnings with no growth in revenues.”

The Magnificent Seven matter immensely at present, then. But that can obscure the fact that at the aggregate level, more companies are surprising compared to their estimates than usual, and that earnings per share are on course to hit an all-time high. This chart from Bankim Chadha of Deutsche Bank AG blends actual results to have been reported so far with forecasts for companies yet to come: (3분기 실적을 발표한 기업과 미발표 기업의 실적 추정치를 더한 수치)

This is in line with what might be expected when the economy is performing better than many had feared. However, Chadha also points out that sales growth continues to decline, even if the very volatile energy sector is excluded, and has has generally disappointed predictions. It’s nothing much to worry about as sales are growing well ahead of historical norms, but does demonstrate that Corporate America isn’t feeling the full effects of a resurgent economy:

Meanwhile, margins are now back to their pre-pandemic peak. On the face of it, this isn’t great news for those worried about inflation, and will feed various negative narratives. It’s impressive that margin growth has been achieved without big job losses to cut wage bills, but suggests that companies aren’t spending that much on things that might help to boost the economy further:

None of this is consistent with a sudden shift toward recession, and thus should support the notion that we are in an interruption to a bull market. But there are more disquieting trends afoot, particularly in the guidance that executives are giving on earnings calls. They are being noticeably downbeat. Chris Watling of Longview Economics in London points out that several of the companies that reported earnings last week chose to highlight “a change in the macro environment in the fourth quarter (i.e. post the cutoff of their earnings report).” Meta was probably the highest-profile example, as it warned about weakness in ad spending (which Watling describes as a classic cyclical indicator that, again, implies companies are cutting back on spending they would otherwise like to make). The huge UK-based advertising group WPP made similar comments.

Watling also drew attention to a negative assessment by the chief executive of Hershey, the big US confectioner:

"Many are cutting back on discretionary purchases, looking for deals, shopping at discount channels, and buying smaller sizes. We have also seen more category and brand switching."

Perhaps most significantly, the shares of TransUnion (미국의 개인 신용 평가 기업) – a credit reporting agency that is heavily leveraged to the flow of consumer – fell by about a third last week after it reported disappointing earnings and withdrew its guidance for 2025. Most damagingly, Watling pointed to the CEO’s comment that: “Cracks have occurred across consumer lending, especially in the lower credit tiers.” The market’s response, which may have been overdone, eliminated all TransUnion’s outperformance of the S&P 500 since its 2015 IPO:

Ultimately, this view from Watling strikes me as very reasonable. The surprising strength of the economy explains the dreadful performance by the bond market — but the evidence is falling into place that that strength won’t last much longer:

"While the macro data is yet to confirm the recession (and indeed was notably strong in the third quarter), other evidence (anecdotal, corporate and yield curve, amongst others) is building."

user error : Error. B.