Rates tend to spike and fall like a Patagonian precipice, but now there’s a Table Mountain theory of a long, flat plateau.

Descending was harder before the cable car. L'Aiguille du Midi above Chamonix, France.

Photographer: Emmanuel Dunand/AFP/Getty

By John Authers

2023년 9월 22일 오후 3:03 GMT+9

Climb Every Mountain

We have a new analogy for monetary policy. Huw Pill, the Bank of England’s chief economist, has given a speech in which he favored a “Table Mountain” scenario. In line with the wide and flat peak behind Cape Town in South Africa, the idea is that rates would reach a plateau, and then stay there for a long time. Under this scenario, according to Pill, rates needn’t go quite so high as in a “Matterhorn” scenario, named for the famously sharp triangular Alpine peak, but they would have to stay at that high plateau for an extended period.

What higher for longer looks like. Table Mountain rising over central Cape Town.Photographer: Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty

This is great comparison on many levels, for reasons that go far beyond giving us an excuse to decorate this piece (of writing) with some beautiful photographs of mountain scenery. Mountaineers say that the greatest dangers are on the descent, not the climb up. It’s at this point that the objective has been met, arms and legs are tired, the brain is perhaps foggy from lack of oxygen, and feet have to be placed downward, toward the void, rather than braced into the cliff face. This is when accidents happen. The same is true of monetary policy.

If there’s one more or less clear signal to unite this week’s global round of central bank meetings (with the eternal exception of the Bank of Japan, which left rates unchanged and still hasn’t started to hike), it’s that by and large they hope they’ve reached a plateau. The Swiss National Bank and the Bank of England sprung significant surprises by opting not to raise rates at all, while last week’s European Central Bank meeting did see a rate rise, but also made a concerted effort to convince the market that it might well be the last. Sweden’s Riksbank hiked to 4% Thursday, but sent strong signals that it was done. So maybe we’ve scaled the top of Table Mountain:

The analogy works all the better because hills shaped like Table Mountain, with a wide flat top, aren’t that common. Triangular peaks are more usual. And if we look at the course of history, we tend not to see Matterhorns, so much as moves more reminiscent of the Torres del Paine, at the southern tip of Chile:

The Three Towers, Torres Del Paine National Park, Patagonia, ChilePhotographer: Piero Damiani/Moment RF/Getty

Now, let’s look at the fed funds rate over the last two decades, and over the fateful 20 years starting in 1971. Rates were altogether higher in the ’70s and ’80s, so they’re on different scales, but the Paine-like shape is common to both:

Mountains Beyond Mountains

Rates in the last two decades, and the 1970s, never hit a plateau

Rates tend to move like this because monetary policy is about tightening until something breaks. If a financial crisis or a recession breaks out, rates will have to come down fast. Measured, Matterhorn-like decreases are unusual. And they will now have further to fall, as these central bank announcements have been accompanied by a significant upward breakout in bond yields. In Asian trading, the 10-year Treasury yield reached 4.5% for the first time since the eve of the Global Financial Crisis in 2007 — the kind of landmark that people in the markets will notice. According to Strategas Research Partners, monetary conditions, broadly defined, haven’t been as tight as this since 2007. Or as the firm’s Tom Tzitzouris puts it, “any time conditions reach this level of tightness, a recession is soon to follow.” He added:

"Part of this tightening was passive; the dot plot indicated yesterday that rate cuts next year are likely to be slower to come.But part of it was simply an acknowledgement by the bond market that until recession hits, yields are going to have to keep rising."

When and if recession does hit, or when high rates at last spill over into the much-feared financial accident, rates tend to make like the Torres del Paine, or the equally spectacular Cerro Torre just over the border in Argentina, and fall away in a sheer cliff:

Sunrise at the Cerro Torre in Glaciares National Park, Patagonia, Argentina.Photographer: mmphoto/Digital Vision/Getty

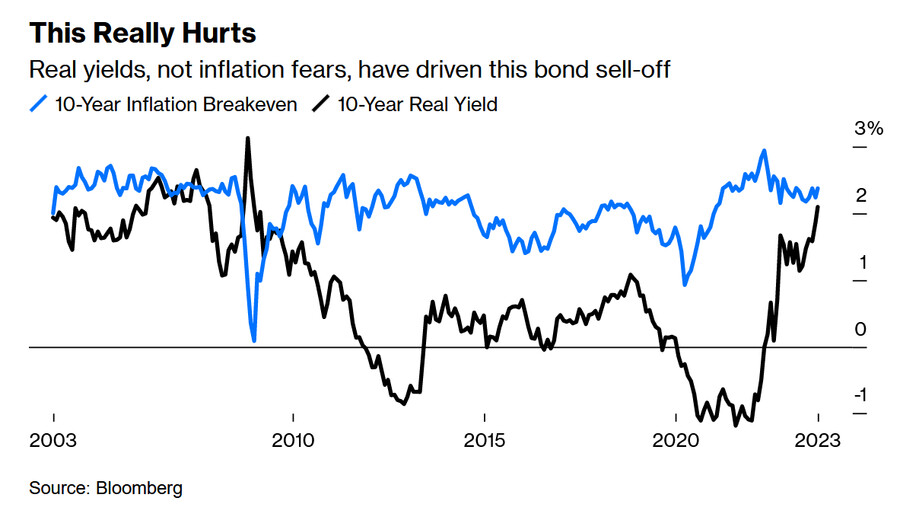

Looking further into the increase in yields shows that this is a genuine tightening. The 10-year yield can be split into a rate to cover expected inflation (the breakeven rate), and a remaining “real yield.” The former responds to alarms about inflation, while the latter can be treated as the driver of whether conditions are truly tight. Substantially all of this year’s move has come from higher real yields, while fears about inflation have actually abated a little:

The latest step upward is roundly attributed to Jerome Powell of the Fed. Matthew Klein of The Overshoot newsletter suggests that the Fed’s projections imply an economy with “more underlying momentum than previously believed *and* that there is less need to crush the job market to bring inflation back into line by 2026.” That means that the Fed’s “bullishness,” as Klein puts it, is pushing up rates. Unless and until the Fed succeeds in “breaking something” — a large institution, or the economy — yields will be under pressure to rise, rather like the Trango Towers in Pakistan, up into the sky.

Penitentes snow formations with the Trango Towers in the background, captured by the great mountaineer Eric Shipton on the Shaksgam Expedition, 1937.Photographer: Royal Geographical Society/Getty

Breaking the Ice

When descending Table Mountain, you don’t usually need to worry about ice. Sadly, the same is not true of many other more famous peaks. And when it comes to investing, ice could be one of the biggest issues for anyone trying to allocate assets.

Logically, higher bond yields should be bad for stocks. Quite apart from denting economic activity (which they don’t seem to have done as yet), they should do this by increasing the rate at which companies’ future earnings must be discounted, and by providing stiffer competition. The better the yield that’s available from bonds, the argument would go, the more yield you will want from a stock before buying it, and that means that the share price should go down.

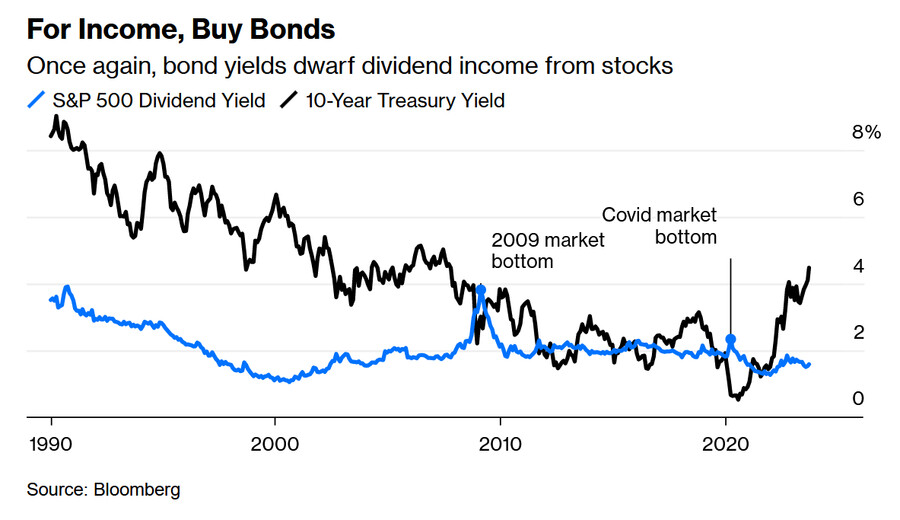

There are many ways to measure this, but the simplest is to compare cash payouts — the Treasury yield against the dividend yield on stocks. In recent years, the only times when the income from stocks actually exceeded that from bonds came at moments that proved to be great buying opportunities for equities, in 2009 and 2020. But the bond yield now exceeds dividend yields by the most since before the GFC. In theory, that should mean that stocks’ yields might need to rise a bit, and hence their prices fall:

One of the more immediate impacts of the breakout in bonds has indeed been a tumble for equities. It would be over-egging(과장하는) it to say that stocks have been through a correction, but momentum has been halted, with the main indexes no longer any higher than they were at mid-year. The S&P 500 is down a little more than 5% from its 2023 peak, and looks more Table Mountain than Matterhorn. But why aren’t elevated bond yields exerting more influence?

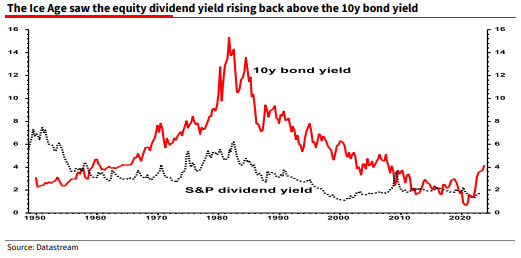

Enter Albert Edwards, famously bearish investment strategist for Societe Generale SA, who promulgated the “Ice Age” thesis back in 1996 and has held on to it. Having witnessed the Japanese slump of the early 1990s, he suggested, even as bond and equity yields fell together, that:

"We would soon reach the point at which equity yields would de-couple and begin to rise despite inflation and bond yields continuing to fall. This meant, among other things, that traditional positive equity/bond correlations would break down and equity investors would pay a higher premium for stocks displaying strong earnings growth and/or earnings certainty."

(Albert Edwards의 Ice Age thesis : 금리가 하락해도 주가는 약세를 보일 것, 버블 붕괴 이후 불황을 겪던 일본 시장에서 나타난 현상)

As the Ice Age took a grip, he argued that the markets were travelling back to the 1950s, when the equity dividend yield was always higher than the bond yield. That was his “new normal.” And indeed, before the Cult of the Equities took hold in about 1960, the orthodoxy was that stocks paid a higher yield (than bonds), to compensate investors for greater risk:

Edwards suggests the really serious problem for stocks now would be a pick-up in inflation breakevens, which could carry bond yields higher. (유가 상승 → 인플레이션 기대 심리 → 채권 수익률 상승)

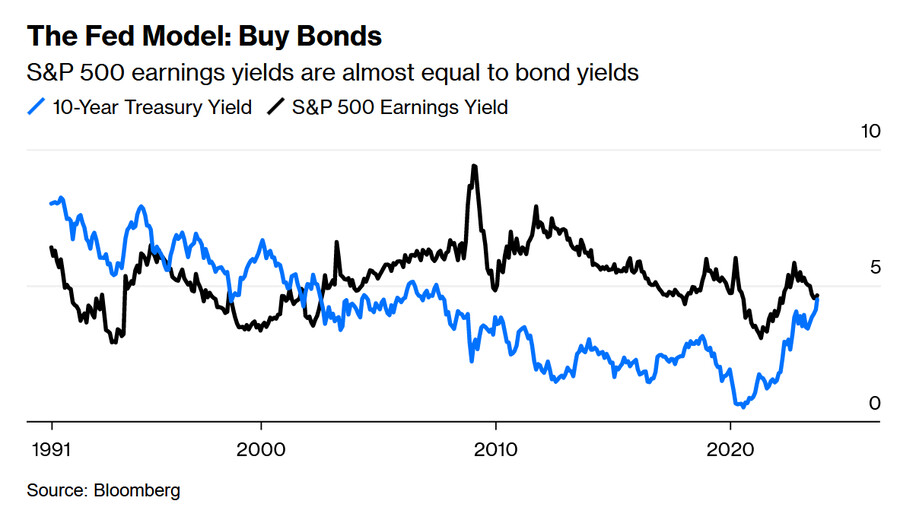

Another famous view of the interaction of bond and stock valuations is the “Fed Model,” so-called because Alan Greenspan appeared to be using it in congressional testimony. The idea is that earnings yields (the inverse of the price/earnings multiple) on stocks should track 10-year Treasury yields. There’s more contention over measuring earnings than dividends, but ultimately you buy a right to future profits when purchasing a share, so this makes sense. There appeared to be a tight relationship in the 1980s and 1990s, and then almost none in this century as bond yields were held down. Now, the two are more or less equal. That suggests buying bonds (for their lower risk):

(주식의 장기 기대 수익률이 채권 수익률과 같다면 주식보다 안전한 채권을 사는 것이 유리)

In classically bearish fashion, Edwards continued: “How much more pain from rising bond yields can equities now tolerate? Maybe none.” And while that might be a little harsh, the arguments in favor of bonds look stronger than they’ve done in a while. People have ample reason not to take more risk than they have to. Bonds now guarantee a reasonable income without capital loss, if they’re held to maturity. And the greatest risk is to the downside in terms of yields, which is bullish for investors hoping to sell for a profit. In other words, previous mountainous experiences suggest that a big fall in yields is more likely than a steep rise in the future, and that would make bonds that much attractive.

(역대 금리 인상 사례에서 알 수 있듯이, 앞으로 금리는 급등보다 급락 가능성이 커 보임. 주식보다 채권이 훨씬 매력적으로 보이는 이유.)

Is this unduly bearish? Mitigating arguments include that bond yields are rising primarily because the economy is in much better shape than thought. That’s good for stocks, and might even outweigh the higher rates. Also, this makes it far easier for retirees to make an income, and should thus boost consumption. Those (generally large) companies that have borrowed at fixed low rates can now make easy money by buying bonds, and that will help their share price. Nothing about asset allocation is as straightforward as it looks, which is why it’s so difficult. Like descending Cerro Torre in heavy clouds.

(반론으로는 ① 경제가 예상보다 좋을 수도 있음 ② 금리가 오르면 은퇴자들의 소득이 늘어 소비도 증가 ③ 팬데믹 당시 낮은 고정 금리로 돈을 빌린 기업들은 채권을 사서 쉽게 돈을 벌 수 있음. ①, ②, ③ 모두 주식에 유리한 점들. 채권/주식 모두 유리한 점이 있기에 자산배분은 보기보다 쉽지 않음.)

Risky conditions.Photographer: Steve Whiston/Fallen Log Photo/Moment RF/Getty