There are benefits to an ‘old-fashioned’ allocation to cash these days, such as optionality and even a good yield.

2023년 9월 29일 오후 2:25 GMT+9

By John Authers

John Authers is a senior editor for markets and Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A former chief markets commentator at the Financial Times, he is author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets.”

Sen. Bob Menendez exits federal court in New York on Wednesday.Photographer: Yuki Iwamura/Bloomberg

Sen. Bob Menendez exits federal court in New York on Wednesday.Photographer: Yuki Iwamura/Bloomberg

Perhaps the Senator Has a Point?

When it comes to asset allocation, Sen. Bob Menendez might just be the one to follow. Indicted on fraud charges after $480,000 in cash was found in his house, the New Jersey Democrat explained: “For 30 years, I have withdrawn thousands of dollars in cash from my personal savings accounts, which I have kept for emergencies and because of the history of my family facing confiscation in Cuba.” He admitted that this might “seem old-fashioned.”

Not all of us regard this explanation with total credulity. And when we talk about “cash,” it’s probably better held in insured bank deposits, rather than in bundles of Benjamins under the floor. This isn’t Cuba; confiscation is unlikely. That said, is there something to be said for an “old-fashioned” heavy allocation to cash?

On top of whatever reasons Menendez has for hoarding cash, there are two key arguments. The first is that it gives you optionality; if you decide the moment has arrived to take an opportunity, you can do so quickly. And second, these days, it pays you a decent yield. Indeed, the yield on three-month Treasury bills now exceeds the earnings yield (the inverse of the price/earnings ratio) that can be received from the S&P 500, for the first time since the dot-com bubble burst at the beginning of this century. It’s also far above the S&P’s dividend yield, reflecting what it will pay you in cold hard cash, again to an extent not seen in more than 20 years:

The bond selloff this month has been one of the most extreme in years, a fact unchanged by a startling reverse in Thursday’s New York trading. It’s true that the 10-year real yield dropped more than 12 basis points in a matter of hours, which is spectacular. It’s also true that by the end of Thursday, the yield, at just under 2.2%, was slightly higher than the level at which it opened Wednesday — the bond market remains unsettled, and the upward trend remains intact for now.

The selloff is also increasingly global. In Europe, the 10-year yields of Italian BTPs and German bunds have jolted upward and are close to the landmarks of 5% and 3% respectively, untouched since the eurozone’s sovereign debt crisis that started in 2010. Both seem to have come untethered in a way not experienced since the “whatever it takes” speech by the then-president of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, began to bring yields under control in the summer of 2012:

Yields are rising in large part because 2023’s economic growth has been far stronger than most expected, especially in the US. By the end of last year, the growth data was coming in line with economists’ predictions after a protracted period of positive surprises in the wake of the recession. But once again, the economy has started to surprise to the upside, as illustrated here by Bloomberg Economics’ US growth data surprise index:

Perhaps because growth still looks so strong, stocks are still performing well enough to outstrip bonds’ performance. In theory, higher income from bonds should tempt some people to sell their stocks, but on aggregate that isn’t happening. Rather, the way to limit the damage so far during this selloff has been to hold on to stocks while shorting bonds. Such a strategy, proxied below by the ratio of the main exchange-traded funds tracking the S&P 500 and Bloomberg’s index of long-dated Treasuries, has carried on without missing a beat, even since the S&P peaked and began to shed some of its gains about two months ago:

To quote Bloomberg Surveillance colleague Lisa Abramowicz, it’s “as if the two markets weren't talking to each other at all, despite their traditional relationship.” She suggested that “stocks and bonds are on completely different pages right now, with equity traders rejecting the message being sent by their fixed-income peers.”

How long can this go on? That depends on the effect that higher bond yields have. Points of Return recently revisited the concept of the equity risk premium, one of the central assumptions of modern finance, which posits that investors demand a premium from stocks to compensate them for the extra risks compared to Treasuries. When bonds become more generous in the return they offer, as now, that implies that all else equal, stocks will have to fall in order to offer a sufficient premium.

Everybody knows that in practice the relationship between stocks and bonds isn’t that simple, that the premium will change from time to time, and that the direction of correlation will move. But the contrast with last year is growing strong. According to Nicholas Colas of DataTrek:

"The dynamic between stocks and long-term bonds is different now than in 2022. Last year, long-dated bonds and stocks sold off together because the Fed was aggressively raising short-term interest rates. This year, the FOMC is mostly done with rate hikes, but the market now understands that the Fed wants to see real long-term interest rates increase further. The problem for stocks is that we don’t know where long rates will settle out, or what effect that terminal rate will have on economic growth and corporate earnings."

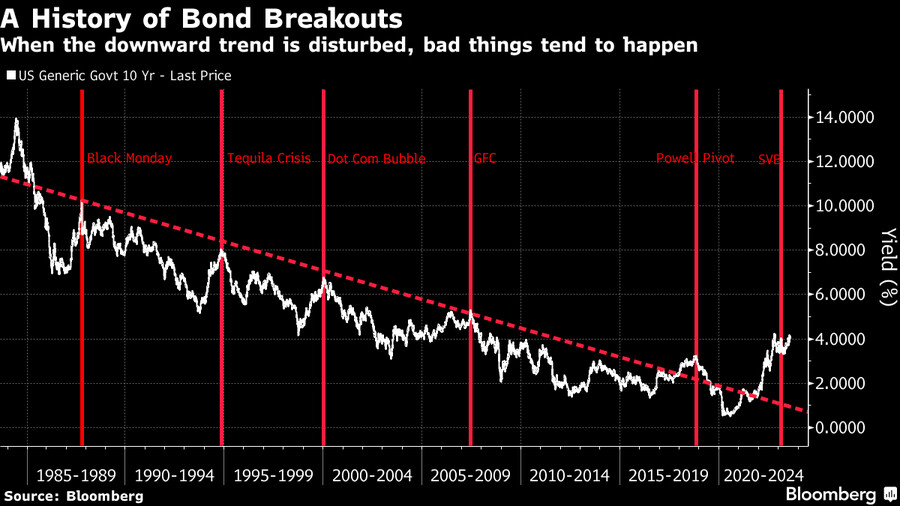

The case for lower long-term yields in future (and hence for buying bonds) goes as follows. What has happened in the past is that higher yields prompt an economic slowdown, which brings down rates and bond yields (thus making money for bondholders), while creating much tougher conditions for stocks. All the rises in bond yields to threaten the steady downward trend that started in the early 1980s have culminated in a major financial accident of some kind, followed by falling yields. Here’s an illustration of the phenomenon that we first published in August:

This implies that the rising yields will soon break something, either the economy or a financial institution. At that point, it’ll be a great idea to buy bonds as their yields plummet, and sell or short stocks. The bond selloff so far has been driven by the belief that the economy is too strong, meaning that equities can still prosper. To be able to do this swiftly when there is greater clarity in the situation, perhaps execute the Menendez Strategy and put money into cash for now.

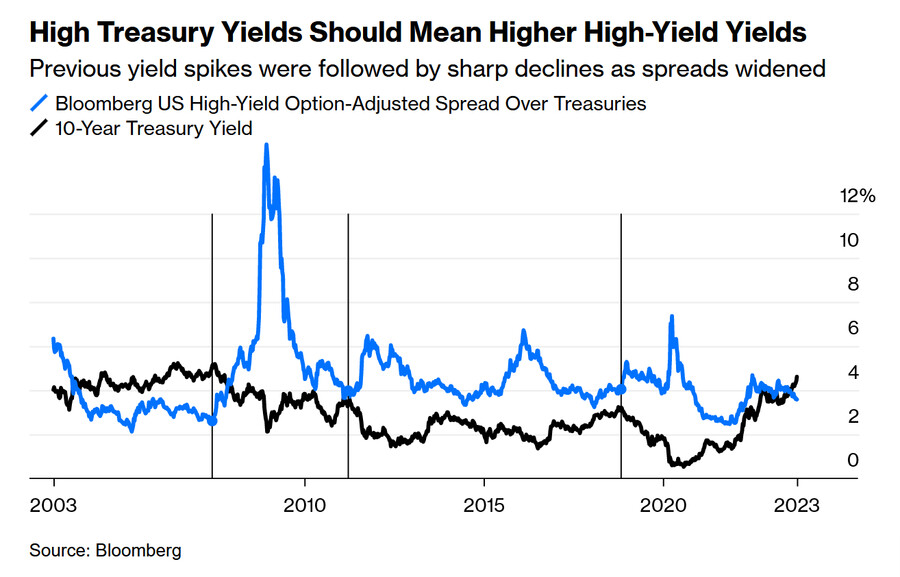

Past experience would certainly argue against making any big move to buy corporate bonds at this point. Another curio of this latest bout of rising Treasury yields is that high-yield — or “junk” — bonds have barely noticed (and the same is true of investment-grade corporate debt). Previous big Treasury yield spikes were followed swiftly by major surges in the spreads of the yields corporate bonds compared to Treasuries. That makes total sense; higher bond yields tend to lead to economic slowdowns, which are really terrible news for highly indebted smaller companies. So far during this incident, however, high-yield spreads have tightened a little. To quote Matt Miskin, co-chief investment strategist of John Hancock Investment Management, “You aren’t being paid much for that credit risk.”

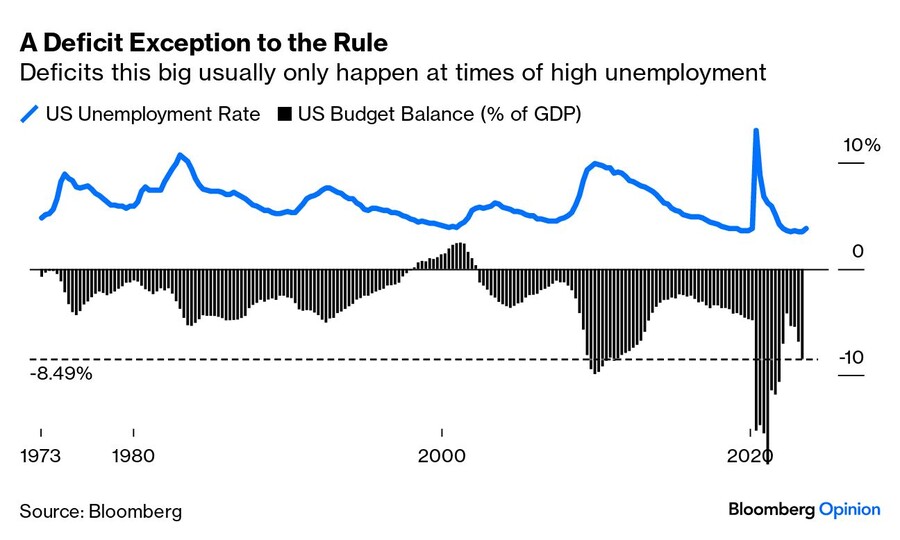

Does this mean that the case for the Menendez Maneuver has been made, and we should shelter in cash (or in Treasury bonds)? There are still some significant downsides, the greatest being the sheer weirdness of the fiscal situation. The revolt in the British gilts market last year, after the administration of Liz Truss unveiled plans for unfunded tax cuts that would have widened the deficit, was a potent signal of how bond markets might revolt. This week’s selloff of European bonds appears to have been catalyzed by aggressive spending plans by France’s Emmanuel Macron and particularly Italy’s premier, Giorgia Meloni. This threatens once again to drive apart the fault lines in the eurozone, which has one monetary policy but many fiscal policies.

It also draws attention to the risks of a bizarre situation in which the economy is strong by normal measures, and yet governments are resorting to heavy deficits. Usually, deficits deepen during recessions as transfer payments to the unemployed increase and the government invests to try to start activity again. In good times, they narrow, or possibly even turn into a surplus. But in the US (and there are similar effects elsewhere), this is that very rare deficit that has been accompanied by historically low unemployment levels:

지금처럼 경기가 좋을 때 정부가 재정 지출을 늘리는 것은 매우 드문 일

불경기에 실업 수당을 지급하고 각종 사업을 집행하기 위해 재정을 지출하는 것이 일반적

If higher yields finally succeed in slowing the economy and pushing up unemployment, what on earth would happen to the deficit then? The risks are there to be seen. If governments in the US or elsewhere respond to a worsening economy with more aggressive fiscal policy, either through tax cuts or extra spending, the risk is that bonds will revolt, much as they did against Truss. That implies a return to the conditions of the 1970s, when bonds were a dreadful investment.

고금리로 경제가 어려워지면 정부는 더 공격적으로 재정을 집행할 것이고 그러면 재정 적자는 더욱 심화될 것 (통화 정책과 재정 정책의 엇박자)

그러면 국채 발행은 늘어날 것이고 국채 수익률은 계속 올라갈 것 (= 국채 가격 하락)

→ 1970년대와 비슷한 상황

Surprisingly, strong support for avoiding bonds comes from the GMO fund management group in Boston, founded by Jeremy Grantham, who these days is known as an equity bear. In the latest GMO Quarterly Letter, his colleagues Ben Inker and John Pease set out an argument to eschew bonds in favor of carefully selected stocks:

"Bonds were an amazing risk hedge during 2008 and Covid, but they did poorly during the inflationary recessions of the early ’80s and were not the boon to performance that one would expect in the Savings & Loan crisis of the early ’90s. If we continue to be in an environment of fiscal largesse, bond supply will increase during the next crisis. At the same time, the odds of experiencing a new bout of quantitative easing are remote, thus taking away the largest inelastic buyer of bonds from the table."

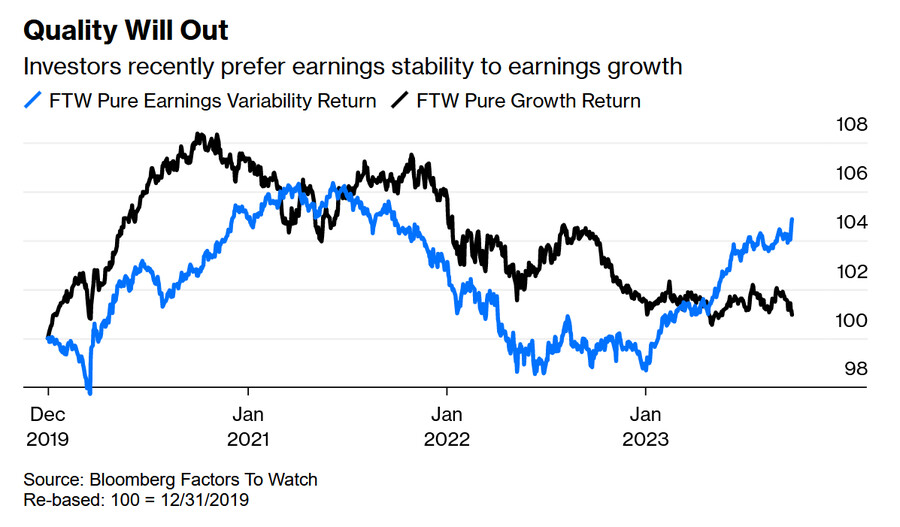

This evidently isn’t a reassuring scenario for the economy. If higher yields beget a slowdown, inflation and more government borrowing, they could go much higher. A 1970s environment like this isn’t good for anyone, but it should be better for stocks than bonds. Thus GMO advocates for stocks, albeit only those of cheap, high-quality companies. There aren’t many of those; generally companies don’t stay cheap for long after people realize that they are high-quality. It’s also notable that they’ve come into favor recently, in a sign that equity investors are rather more negative about the economy than the strong headline indexes might suggest. The following chart is produced using the Bloomberg Factors That Work function (FTW

고금리로 인한 경기침체, 재정 적자 증가(=국채 발행 증가), 인플레이션 환경

→ 싸고 퀄리티가 높은 주식이 채권보다 유리함

블룸버그 자료에 따르면 올해 고퀄리티(이익 변동성이 낮은) 주식이 성장주를 아웃퍼폼하고 있음

If you think it’s possible the Fed will fail to curb inflation, then bonds’ yields go higher and stocks will beat them. If on the other hand, your guess is that these higher rates do the trick, either via an accident or inducing a recession, then bond yields go down and you want out of stocks. Either way, amid a confused situation in which Covid has rendered most precedents inadequate, it’s good to hold some cash. But don’t pile up the banknotes like Bob Menendez allegedly did or you might attract unwanted attention.

① 연준이 인플레를 잡는데 실패할 경우

→ 채권 수익률 상승(채권 가격 하락), 주식이 채권을 능가

② 연준이 인플레를 잡는데 성공할 경우 (금융사고 or 경기침체)

→ 채권 수익률 하락(채권 가격상승), 채권이 주식을 능가

— Reporting by Isabelle Lee