블룸버그 기사 요약 (ChatGPT) (1/2)

John Authers의 기사는 미 정부의 최근 동향과 금융 시장, 특히 채권 시장에 미치는 영향에 대해 논의합니다. 다음은 주요 내용입니다.

정부 셧다운 방지: 기사는 세계 최대 경제인 미 정부가 셧다운을 피하고 적어도 11월 중순까지 열릴 것이라고 언급합니다. 그러나 저자는 미국의 정치적 상황을 고려할 때 이를 반드시 좋은 소식으로 보지 않는다고 지적합니다.

시장 영향: 기사는 하원 민주당 의원들의 도움으로 간신히 임시 예산안을 통과시킨 것이 시장을 놀라게 했지만 금융 시장에 큰 영향을 미치지 않을 수도 있다고 제안합니다. 월가의 전반적인 반응은 부정적이며, 전문가들은 정치적 기능 장애가 정부에 대한 신뢰를 떨어뜨릴 수 있다는 우려를 표명합니다.

금융 효과: 정부 셧다운을 피했음에도 불구하고 기능 장애와 정부 채무에 대한 우려는 금융적 영향을 미쳤습니다. Cumberland Advisors의 David Kotok은 정치적 기능 장애가 (정책 금리가 아닌) 시장에서 결정되는 금리를 상승시키고 채권 스프레드를 확대하는 등 금융 상태에 부정적인 영향을 미쳤다고 강조합니다.

채권 시장 상황: 기사는 최근 채권 시장의 변동성과 수익률 급등에 대해 의문을 제기합니다. 이에 대한 잠재적인 설명은 다음과 같습니다.

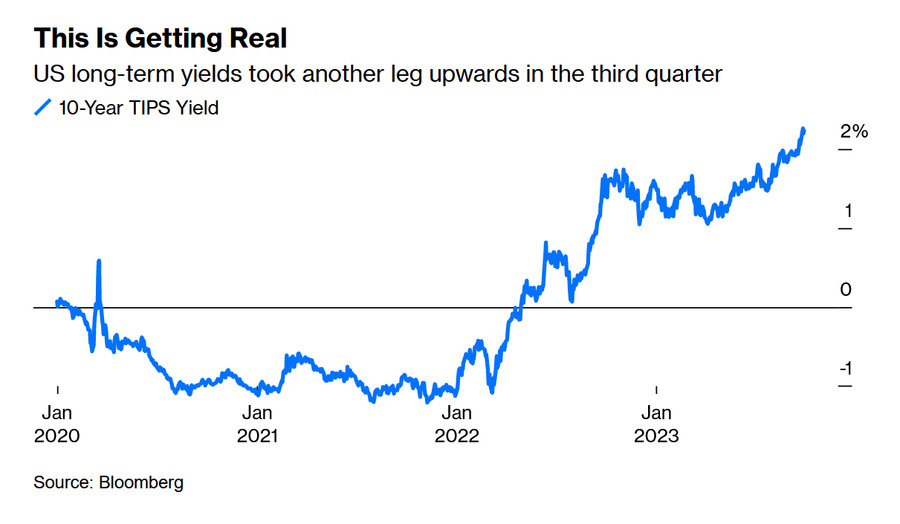

a. 인플레이션: 기사는 최근 인플레이션 데이터가 예상보다 낮았기 때문에 인플레이션은 채권 수익률 상승의 원인이 될 수 없다고 말합니다.

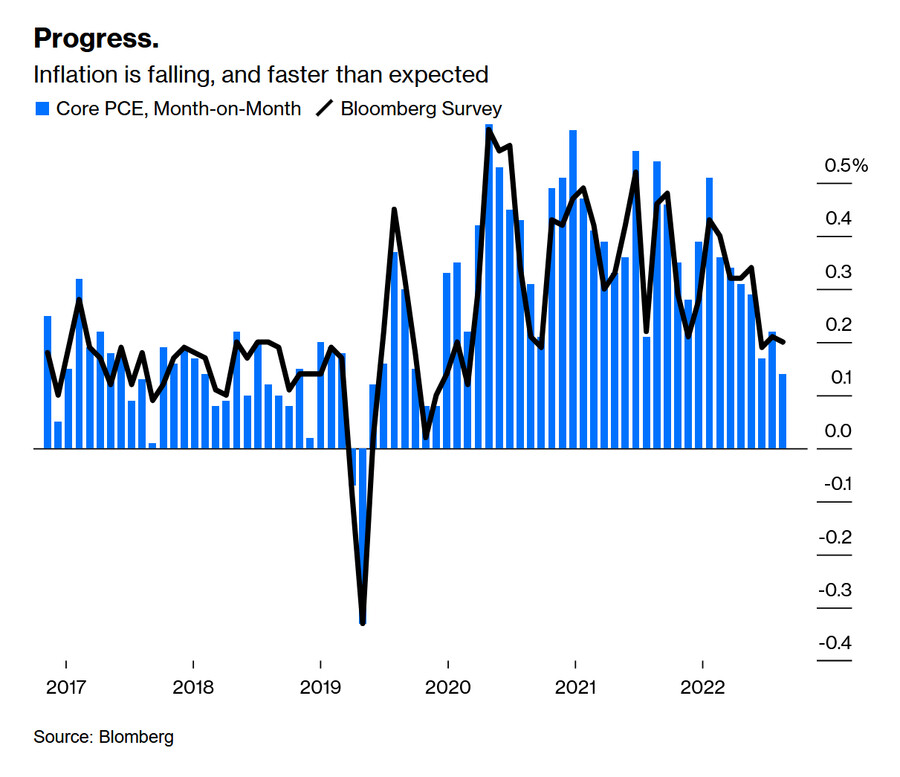

b. 경제 전망: 경제에 대한 큰 낙관론이 없으며, 많은 자산 배분 투자자들은 향후 12개월 내에 경기 침체가 시작될 것으로 예상합니다.

c. 유동성: 미국 정부는 더 많은 채권을 발행할 가능성이 높으며, 이는 투자자들이 더 높은 수익률을 요구하고 기간 프리미엄을 증가시킬 수 있습니다. 기간 프리미엄은 투자자들이 장기 채권에 투자할 때 요구하는 위험에 대한 보상입니다.

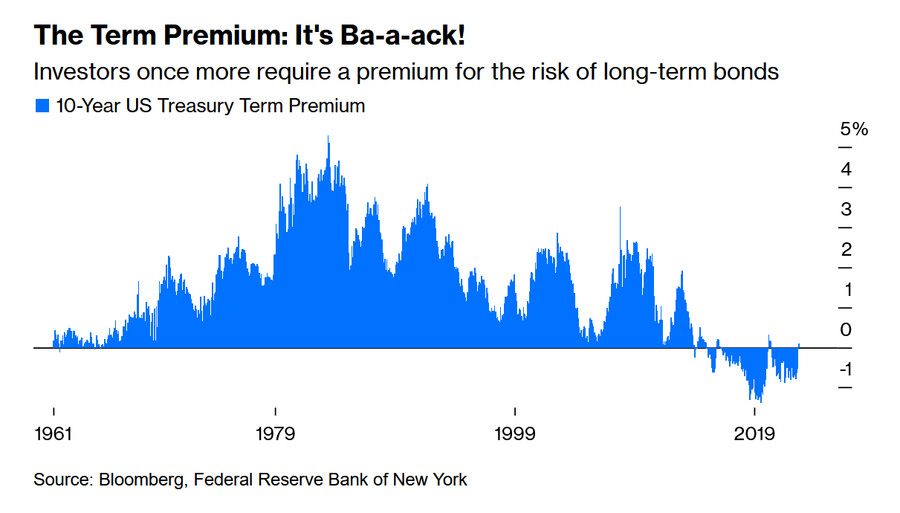

기간 프리미엄: 최근에 마이너스였던 기간 프리미엄이 다시 플러스로 돌아섰습니다. 이는 투자자들이 더 높은 금리 예상, 미국 재정 적자에 대한 우려, 외국 투자자 수요 감소 등의 요인으로 인해 장기 채권 보유에 대해 더 높은 보상을 요구하고 있음을 시사합니다.

기간 프리미엄 상승에 기여하는 요인: 기간 프리미엄 상승에 기여하는 요인으로는 미국 연방준비제도(Fed)의 양적 강화(QT) 축소, 중국의 미국 국채 보유량 감소, 미국 재무부의 자금 조달 수요 증가 등이 있습니다.

결론적으로, 기사는 미국 정부가 정부 셧다운을 피했지만 정치적 기능 장애와 정부 채무에 대한 우려가 금융 시장, 특히 채권 시장에 영향을 미치고 있다고 강조합니다. 기간 프리미엄이 다시 플러스로 돌아섰다는 것은 투자자들이 장기 채권 보유에 대해 더 높은 보상을 요구하고 있으며, 이는 수익률이 더욱 상승할 수 있음을 시사합니다. 정치가 현재 시장 상황의 유일한 원인은 아니지만 도움이 되지는 않다고 저자는 말합니다.

==================================================

(Bloomberg) Shutdown Is Shut Down, But Not the Dysfunction

Fiscal-cliff drama in the US government is already priced into the market. More worrying is what’s happening in bonds.

2023년 10월 2일 at 오후 1:49 GMT+9

By John Authers

John Authers is a senior editor for markets and Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A former chief markets commentator at the Financial Times, he is author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets.”

See you back here in seven weeks.Photographer: Anna Rose Layden/Bloomberg

Shutdown Shut Down: So What?

Great news: The government of the world’s largest economy has not closed down, and will stay open at least until the middle of November. That is what passes for good news about US politics these days, and you can see why people aren’t terribly impressed.

As trading closed last week, the assumption was that the government would indeed shut down. Saturday’s dramatic turnaround, in which the Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy decided to push forward with the help of Democrats’ votes to pass a stopgap spending bill, was a surprise but seems unlikely at first glance to have much impact on markets.

Canvassing Wall Street opinion on Sunday, my colleagues found it hard to identify anyone who actually felt positive about this development. Dan Suzuki of Richard Bernstein Associates asserted that “this just delays the pain until November, and in the meantime, the political circus will probably ramp up and further corrode people’s confidence in the government.” Steve Sosnick of Interactive Brokers also damned the news with faint praise, saying: “It’s not as though markets seemed overly concerned about the prospect of a shutdown, so they won’t be euphoric about kicking the can down the road for 45 days.”

However, that isn’t to say that the dysfunction, and the concern about government borrowing that is the nominal cause of this latest spat, is not having a financial effect. For a potent and quantitative condemnation that these political hijinks are having on markets, and will ultimately have on the real economy, you can’t do much better than this assessment from Cumberland Advisors’ David Kotok:

"I’ve written about how the dysfunctional politics in America are raising market-based interest rates even as the Federal Reserve is on “hold.” I’ve cited the widening spread between the 30-year federal agency yield (정부 기관 채권) versus the 30-year US Treasury (재무부 채권) yield. I’ve cited how the credit insurance cost on the United States (10-year credit default swap denominated in euro) is now as high as it was at the peak of the debt ceiling fight last May. Also note that the five-year US dollar-based credit default swap has doubled from 20 basis points to 40 basis points since Jan. 1. I’ve noted the beginning of widening credit spreads on various types of financing. These are market-based prices. These are my not my assertions or opinions. Anyone who thinks that political dysfunction doesn’t have a cost is ignoring the facts."

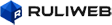

Very true. As Kotok says, the US political system’s inability to get things done is now largely priced in. That, combined with the fact that the latest deal only extends the agony until Nov. 17, means that things aren’t going to shift much. But it does raise fascinating questions about the bond market, which ended the third quarter in riot conditions, in the US and elsewhere. How much of Kotok’s list of bad things happening to financial conditions can be attributed to politicians? Just as a reminder, this is what’s happened to the 10-year government yield since the pandemic:

Beyond politics, what can account for this? The following explanations aren’t mutually exclusive:

Inflation

It’s hard to say that this is about inflation. Last week ended with new core personal consumption expenditure deflator numbers (the Fed’s preferred inflation yardstick) for the month of August. On a month-on-month basis, inflation was the lowest since 2020, and comfortably below expectation. It’s not a reason for bond yields to be rising:

As for inflation expectations, they’ve made no significant moves higher of late, either among market traders or consumers.

Economic Expectations

Meanwhile, it’s also hard to say it’s about any great optimism on the economy. The latest quarterly edition of Absolute Strategy’s regular survey of global asset allocators is now available, and shows that most respondents expect a global recession to start within the next 12 months. It’s true that an even higher percentage previously expected that recession would have started before now, but the point remains that this is not the fuel for a big rise in bond yields:

The rest of the report is characterized by what might be called extreme ambivalence. Like most of the rest of us, big global asset allocators aren’t sure they can explain what is going on. That would normally argue against big moves, such as we’ve just seen in the bond market, and if anything would create a bias toward risk aversion, which would imply buying bonds, not selling them.

Liquidity

This brings us back, arguably, to the problem of the government’s deficit. The likelihood is that the US is going to be issuing a lot more debt. That then threatens to prompt investors to demand a higher yield in return for buying more of it, irrespective of their view of the economic prospects. And that means demanding a higher term premium.

The term premium is a concept that can’t be nailed down in real time (much like the equity risk premium); but that doesn’t stop people from trying to calculate it. One simple way to define it is the extra yield that investors require for the risk of investing over a long term. Points of Return doesn’t cover it often because it’s fiendishly technical and difficult to write about. This newsletter from last year gives some of the definitions.

This schema from the liquidity guru Michael Howell at CrossBorder Capital gives the intuition behind it. A long bond’s yield can be split into the expected terminal rate and something extra to compensate for the risk of investing for longer. If there’s an expectation that interest rates will stay higher for longer along the way, that will also increase the yield. What’s left is the term premium. This is his version:

Howell’s stark verdict is as follows:

"This is not (yet) a credit crisis like the 2008/09 Global Financial Crisis. Nor is it (yet) a full-blown recession caused by over-tightening by central banks. Rather it is a duration crisis resulting from a lack of willing buyers of longer-dated debt. This crisis coincides with the downgrade of US debt by rating agency Fitch and projections by the US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) that the US public debt/GDP ratio will exceed a whopping 200% within the next quarter century."

The most widely cited version of the term premium is published by the New York Fed, and has been calculated back to 1961. Normally, it is substantial because people need to be compensated. Of late, very unusually, that premium has been negative — but it’s just turned positive again:

The logical next step would be for the term premium to return to something like its normal level, which would entail a big further rise in yields (providing expectations for inflation and Fed funds don’t drop.) Why is this happening? According to Sonia Meskin, head of US macro at BNY Mellon Investment Management:

"The US Treasury term premium turned positive last week, which means investors are asking for higher compensation to hold longer-dated securities. While the term premium is not directly observable, we know it is driven by several factors, including: expectations for higher level of rates and rate volatility; concerns around US fiscal trajectory; and slower foreign investor demand precisely at the time when the US Treasury funding needs rise."

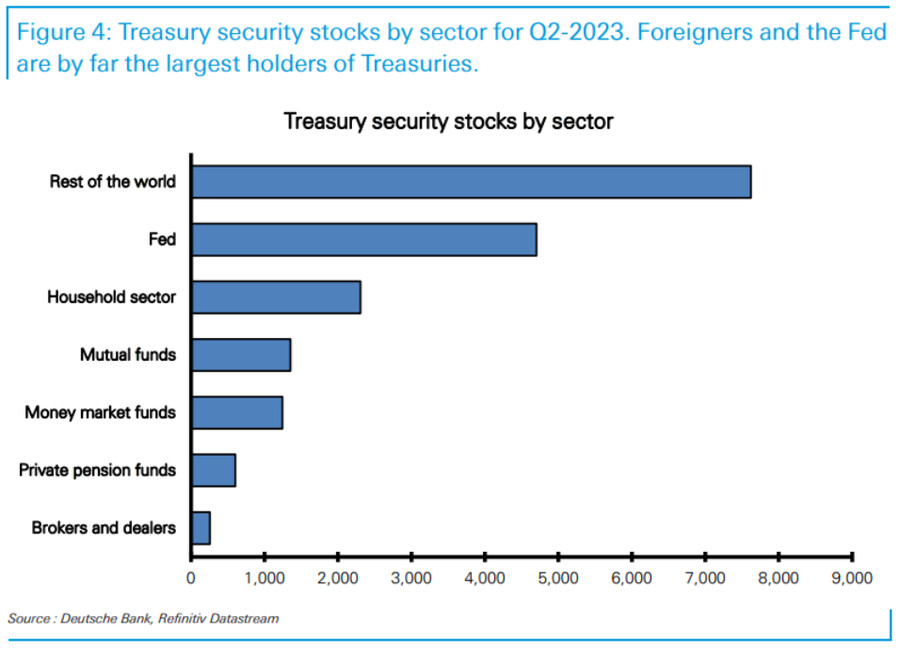

These are the owners of US Treasury debt at present, in a chart from Deutsche Bank AG’s Alan Ruskin:

The Fed has advertised its intention to reduce its holdings through quantitative tightening (QT, or selling off bonds from its vast portfolio to take cash out of the system and tighten financial conditions). China is reducing its holdings and may need to draw on its reserves more if it wants to stop its currency from weakening. The risk that the term premium continues to increase, even without any shift in rates or inflation expectations, looks significant. It’s not all the fault of the politicians, but they’re not helping.

— Reporting by Isabelle Lee

==================================================

블룸버그 기사 요약 (ChatGPT) (2/2)

John Authers의 기사는 정치가 대체 에너지 시장에 미치는 영향과 최근의 발전 동향이 투자자 심리와 에너지 전망에 미치는 영향에 대해 논의합니다.

주요 내용은 다음과 같습니다.

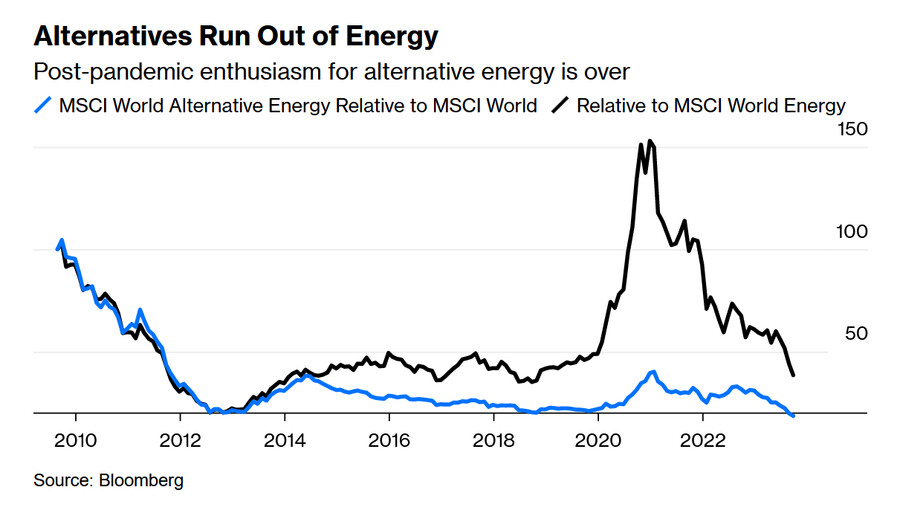

대체 에너지 지수의 실적: 기사는 MSCI World 대체 에너지 지수(World Alternative Energy Index)의 실적에 초점을 맞춥니다. 이 지수는 광범위한 MSCI 월드 지수(MSCI World Index)에 꾸준히 뒤처지고 있습니다. 재생 에너지에 대한 투자 열기가 높음에도 불구하고, 대체 에너지 지수는 최근 광범위한 시장 대비 새로운 최저치를 기록했습니다.

코로나19 이후 급증: 대체 에너지 투자는 코로나19 동안 큰 폭으로 증가하여 2020년에는 전통 에너지 지수를 능가했습니다. 그러나 이러한 능가 성과는 이후 되돌려졌습니다.

자본 비용: 자본 비용이 상승하고 있으며, Gavekal Research의 Louis-Vincent Gave는 저금리 환경에서 미덕에 대한 호소만으로 주도되었을 수도 있는 대체 에너지 프로젝트가 금리가 오르면서 더욱 면밀히 검토되고 있다고 제안합니다.

정치적 불확실성: 정치는 재생 에너지 수요에 중요한 역할을 하며, "넷 제로" 목표는 포퓰리스트 정치가들에게 공격 받고 있습니다. 기사는 스위스가 배출 감축 목표를 거부한 국민투표와 보리스 존슨이 설정한 "넷 제로" 목표에 대한 영국독립당의 정치적 반대와 같은 예를 언급합니다.

정책 반전: 기사는 2030년으로 예정되어 있던 신규 휘발유 및 디젤 자동차 판매 금지가 2035년으로 연기된 영국의 놀라운 정책 반전을 지적합니다. 이러한 변화는 기후 변화 방지 정책에 대한 정치적 기류가 변화했음을 반영합니다.

투자자에 미치는 영향: 정치적 역학의 변화와 기후 변화 정책의 불투명한 미래는 정책 입안자와 투자자 모두에게 시사점이 있습니다. 기사는 "넷 제로" 달성과 재생 에너지의 광범위한 도입이 기정사실이라는 가정을 재고해야 할 수도 있다고 제안합니다.

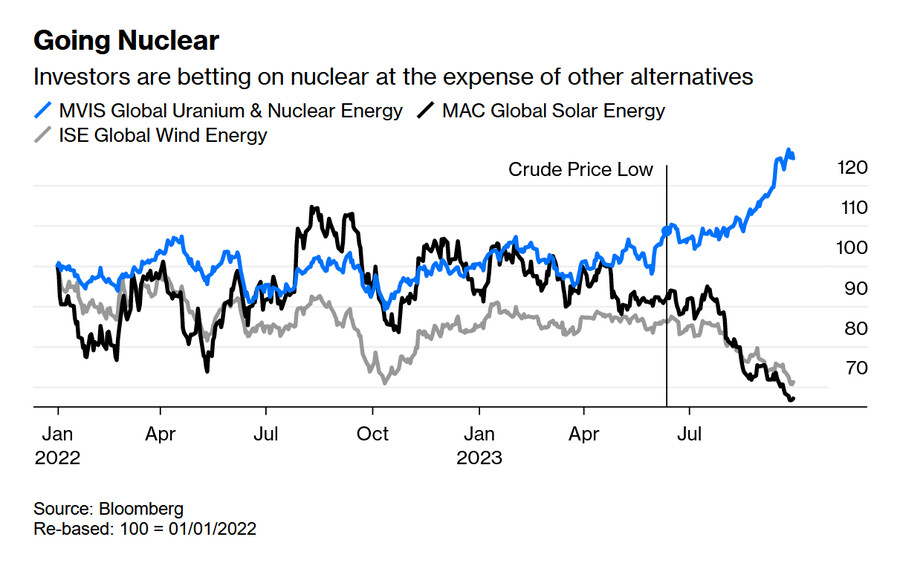

핵 에너지의 부상: 핵 에너지는 "넷 제로"에 대한 정치 역학 변화 및 유가 상승으로부터 혜택을 받고 있는 것으로 보입니다. 투자자들의 핵 에너지에 대한 관심이 다시 증가하고 있음을 알 수 있습니다. 이는 태양광 및 풍력 에너지 주식에 대한 핵에너지 관련 주식의 상대 실적에서 볼 수 있습니다.

핵 산업의 부활: 핵 에너지는 2011년 후쿠시마 원자력 사고 이후 에너지 섹터 전체를 능가했습니다. 이는 핵 에너지가 실행 가능한 대안으로서 다시 관심을 끌고 있음을 보여줍니다.

요약하자면, 기사는 정치, 금융 상황 및 투자자 심리 간의 복잡한 상호 작용을 대체 에너지 분야에서 강조합니다. 최근의 정치적 변화와 기후 변화 정책을 둘러싼 불확실성은 에너지 전망을 재편하고 있으며 이 부문의 투자 전략에 대한 보다 면밀한 검토를 촉구하고 있습니다.

==================================================

Where Politics Is Moving the Needle

If politics isn’t having much clear impact on broader money markets as yet, it’s having a huge effect on the market for alternative energy. MSCI, the index provider, has had a World Alternative Energy index since 2009. It has persistently lagged the broader MSCI World, despite all the hype around the need to invest in renewables. It recently subsided to a new low relative to the broader market, which it has now lagged more than 80% since inception:

Alternatives did get a great boost during the pandemic. They massively outperformed MSCI’s broader world energy index in 2020. But the alternatives index has now given up all of that outperformance. Some of this is attributable to the oil price; if oil prices fall, as in dramatic fashion in early 2020, then conventional energy groups’ ability to make money will be compromised. Alternative energy will look better by comparison. When oil rises, as now, alternative energy is less tempting. With the Russia-Saudi Arabia accord set to raise the price of crude considerably, or even “weaponize” it, that might appear to give even more oomph to plans to invest in alternative energy.

However, the energy market doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Financial conditions have changed, and so have the costs of waiting a while for results, as is necessary when investing in renewables. Louis-Vincent Gave of Gavekal Research, a skeptic of alternative energy, makes the point:

"Embracing lofty alternative energy goals was fine when states enjoyed unlimited funding at near-zero interest rates. In such an environment, why not placate single-issue voters with expensive promises? But this dynamic changes rapidly once capital is no longer free. So perhaps the simplest explanation for the alternative energy face-plant is that in a world in which the cost of capital is on the rise, projects whose returns consist largely of virtue signaling go out the (Overton?) window.---------"

Many will disagree that the returns on solar or wind energy are largely about virtue signaling, but the fact that interest rates are meaningful again does force more scrutiny. Even those who regard combatting climate change as essential suggest, like the Bank of England’s Megan Greene, that attempts to move to the energy transition could constitute a “supply shock” to match that of the 1970s. Tighter money makes it that much harder to pay for the measures needed to deal with that shock.

And then there’s politics. The demand for renewables — whether motivated by virtue signaling or fear of a looming climate catastrophe — is in question, and “Net Zero” is increasingly in the eye of populist political attacks. This isn’t just about the US, where even the science underlying global warming is open to political contest.

Very unpopular during a cost-of-living crisis.Photographer: Jason Alden/Bloomberg

In 2021, a Swiss referendum narrowly rejected a target to halve emissions by 2030. And in March last year, the architect of the Brexit referendum began to call for another referendum on whether the UK should maintain the “net zero” (zero net carbon emissions by the year 2050) target set by then-prime minister Boris Johnson. Nigel Farage, former leader of the UK Independence Party, has made this his new issue. Perhaps crucially, the ruling Conservatives held on to the parliamentary seat of Uxbridge, vacated by Johnson, in a June special election after fighting the contest almost exclusively on the Labour mayor of London’s intention to include it in the city’s “Ultra-Low Emission Zone” (ULEZ). This introduces charges for driving cars in an area of London less well-served than others by public transport, and it’s very unpopular. ('노후공해 차 진입시 2만원 부과' 런던 전역 확대에 시민들 반발이 커지는 상황)

That has now led to a startling reversal by the prime minister, Rishi Sunak, which took the City of London completely by surprise. While the UK remains committed to “net zero” by 2050, according to Sunak, he has shifted back many targets — in particular, a ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars is being delayed to 2035 from 2030.

The latest polls suggest that Sunak is a very long shot to hold on to power at the next general election, which must be held by January 2025. But the point is clear. If even a technocratic mainstream Conservative like him has decided that opposing anti-climate change policies is the way to go, then we should rein back on the assumptions that net zero and the adoption of renewable energy are a fait accompli. That changes the picture for policymakers and investors alike.

A beneficiary of the rise in the crude price and the political turn against “net zero” appears to be nuclear power. This chart, adapted from one by Gavekal, compares the MVIS Global Uranium & Nuclear Energy index with the MAC Global Solar Energy and ISE Global Wind Energy indexes. The move to nuclear stocks over the last quarter, as interest rates and oil prices rose while the rest of the stock market fell, has been startling:

Remarkably, nuclear stocks have now comfortably outperformed the energy sector as a whole since the Fukushima nuclear accident in early 2011, which at the time appeared to signal the death knell of the industry. That notion proved to be premature. Whatever assumptions we had been making about the energy future 12 years later, it looks like they’re also now being re-examined.