블룸버그 기사 요약

1987년에 미국 금리 상승과 연방 정부 재정 적자 증가로 증시 고평가 우려가 고조되던 중 10월 19일 월요일에 S&P 500 지수가 30% 폭락 (블랙먼데이)

이에 일부 전략가들은 현재와 1987년의 유사점을 지적하며 채권 시장이 안정되지 않으면 증시가 블랙먼데이 때처럼 붕괴될 가능성을 우려

저자는 현재 상황이 2013년 '테이퍼 텐트럼(taper tantrum·긴축 발작)과 비슷해 보이기도 한다는 반론을 제기

당시 파월 의장이 양적 완화 축소(테이퍼링, 자산 매입 축소) 가능성을 내비치자 금융 시장 혼란 발생

(미국 국채 금리 급등 및 주가 급락, 신흥국 주가 및 통화가치 급락)

결국 연준은 테이퍼링 시행을 연기할 수밖에 없었음

여기서 얻을 수 있는 교훈 = 금리가 급등하면 통화 당국은 좀 더 유화적이 될 수밖에 없다는 것

올해처럼, 미국 국채 금리 급등에도 주가는 양호한 흐름을 지속하는 것은 매우 드문 일

이런 상황에서 주식 또는 금리가 곧 꺾일 거라고 보는 것이 합리적

① 주가 급락이 벌어질 수도 있고 (1987년 블랙먼데이)

② 금리 급등으로 문제가 발생하여, 연준이 완화적으로 돌아설 수도 있음 (2013년 테이퍼 텐트럼)

美 금리 상승, 재정적자 확대…1987년 블랙먼데이 닮은꼴[오미주]

https://news.mt.co.kr/mtview.php?no=2023100414371363061

===========================================

Comparison for bond yields bear a scarily unwelcome resemblance to 36 years ago. Meanwhile, Japan tries a Verdun strategy.

2023년 10월 4일 오후 2:20 GMT+9

By John Authers

John Authers is a senior editor for markets and Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A former chief markets commentator at the Financial Times, he is author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets.”

Traders look at numbers on a screen on Black Monday, when the Dow plunged 508 points.

Photographer: Anthony Pescatore/New York Daily News Archive/Getty

1987 And All That

In financial circles, comparisons to 1987 are never welcome. The Black Monday crash in October of that year is still the single most terrifying day in market history; any suggestion that current circumstances are at all like the early months of 1987 is a little scary. So it’s disconcerting to findthree references to that inauspicious yearin my email inbox.

True, one is from Albert Edwards, the long-time very bearish investment strategist of SocGen. But he’s not the only one to see something reminiscent of 1987 in 2023’s rally for equities even as bond yields rose. “When I started in the business in 1987,” reminisces Steve Sosnick of Interactive Brokers, “bonds were mired in a bear market for most of the year while stocks rallied sharply. Until, of course, that reversed quickly.”

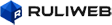

To illustrate just how quickly yields reversed on Oct. 19 when the stock market tanked 20%, and how similar it looks to 2023, here’s an overlay chart of the percentage increase in the 10-year yield from the start of each year:

Chris Verrone of Strategas Research Partners sees “shades of 1987.” Treating Sept. 20 (when Jerome Powell surprised the market with his hawkishness after an Federal Open Market Committee meeting) as a “breakout day” analogous to Aug. 27, 1987, when yields broke upward, he calculates that they peaked 33 trading days later on Oct. 15 at 10.23%. Today, he says, “that would be the equivalent of roughly 5% on the 10-year by early November.”

As for Edwards, he said:

"The equity market’s current resilience in the face of rising bond yields reminds me very much of events in 1987, when equity investors’ bullishness was eventually squashed. And in a further parallel, currency turbulence in 1987 played a key role in exacerbating recession worries for an equity market priced for the start of a new economic cycle. Just like in 1987, any hint of recession now would surely be a devastating blow to equities."

For more horror chart porn, we can move on to equities. This is how the Nasdaq-100 has fared so far this year, compared with how the Dow Industrials did from the beginning of 1987. This is normalized; there’s no trickery with double scales or anything:

Should anyone deploy any money on the basis of overlay charts like this? Of course not. The illustration above does not prove that the Nasdaq will crash next Monday. Starting points for these charts are arbitrary, and all other conditions may not be the same. That said, they can spook people. Particularly when, as now, stocks have run into trouble. Ahead of Black Monday in 1987, versions of the following chart were circulating on Wall Street. One line shows the Dow Industrials starting on Halloween 1986, while the other is the Dow starting on Halloween 1928. Again, they’re indexed:

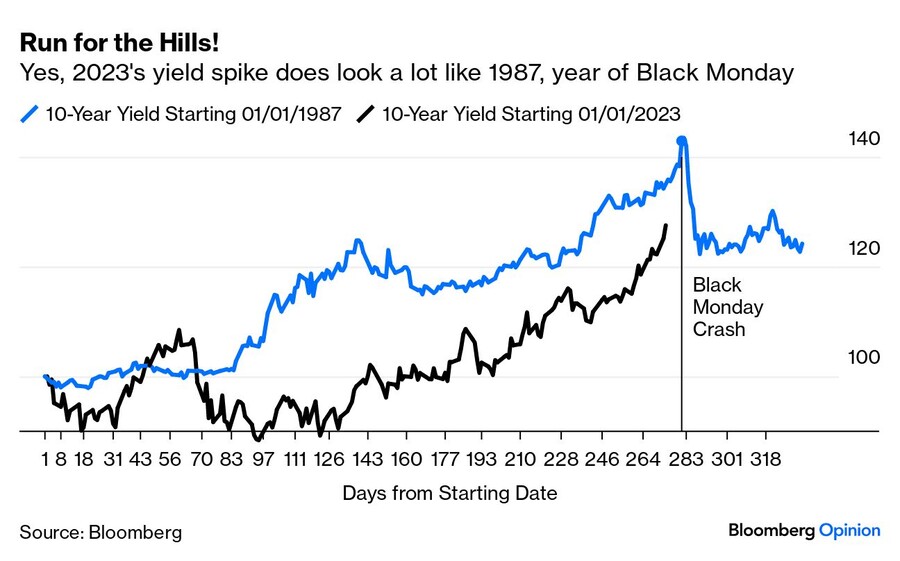

If all this suggests that the equity market will soon inevitably collapse under its own contradictions, I now have a counter-example. This year’s rise in real yields is phenomenal, and is now fully comparable to the Taper Tantrum of 2013, when the bond market fell out of bed at the merest hint from the Federal Reserve that it might slowly start to buy slightly fewer bonds each month. At this stage, the 10-year TIPS yield has gained almost exactly as much as it had by the same point in 2013:

Note that we are now at the point when the first tantrum began to calm down. That was mainly because the Fed decided not to taper its bond purchases in September 2013, to widespread relief and surprise, and instead waited another three months. The lesson from this analogy would be that a spike in yields this dramatic must surely push the monetary authorities into being more lenient.

The lesson from all these charts is that it is indeed very unusual for stocks to perform so well when bonds are having such a bad time. It’s reasonable to expect that something will give soon. It doesn’t necessarily have to involve a stock market crash.

Earnings

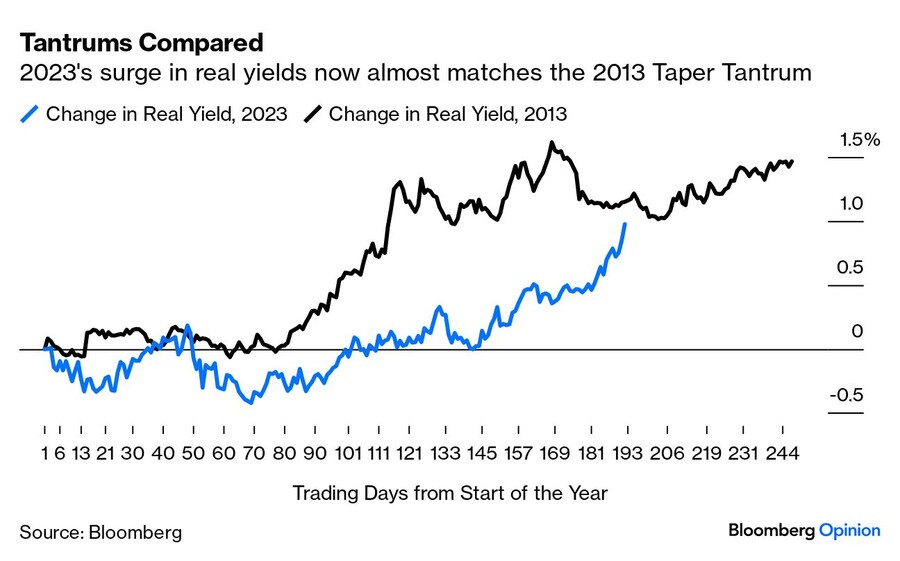

If you want a good reason why stocks won’t crash, it might come from corporate earnings, which in the US are expected to be rosy. Indeed, it’s as though the high inflation, rising interest rates and disappointing Chinese reopening of the last 18 months never happened. As of this week, expected 2023 earnings per share for the S&P 500, as calculated by Bloomberg, topped the peak it made in June 2022:

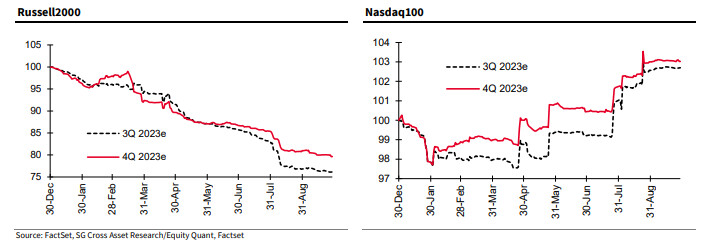

Note, however, that the optimism is not in any way uniform. As the following chart from Societe Generale SA’s chief quantitative strategist Andrew Lapthorne shows, earnings expectations have risen steadily for the Nasdaq-100, dominated by mega-cap technology groups, even as they have plummeted for the small caps in the Russell 2000, for whom third-quarter forecasts are now almost 25% lower than at the start of the year:

Executives themselves seem more comfortable in guiding the Street after three pandemic-distorted years when many opted to stay silent ahead of the results. That said, the greater clarity is not necessarily a good thing, as many are thinking negatively. Of the 115 S&P 500 companies that have given guidance — the highest total number since the first quarter of 2020 — around 24% have revised their projections upwards in contrast to the 39% that changed their projections lower, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

This is why BI’s Wendy Soong expects the reporting season not to be “too bullish” since the company guidance momentum, which basically takes the number of companies who revised upwards minus those that changed lower, is positive. “The predictions for the second half of 2023 ease earnings recession concerns to resumption of growth,” said Soong, who added that estimates also saw moderate growth into 2026.

According to the count kept by SocGen’s Lapthorne, US earnings momentum has cooled in the last few weeks, although a slight majority of revisions are still positive. Globally, momentum remains weak — and it’s also notable that companies are more likely to downgrade estimates for 2024 than for this year, possibly a result of the increasing belief that rates will be “higher for longer”:

To Raphael Thuin, head of capital markets strategies at Tikehau Capital, the consensus is too optimistic. “People are estimating the economy will rebound and that we won’t have a recession. That’s too optimistic. You don’t need a crystal ball. There is a liquidity risk,” he said, referring to the decreasing money supply, or M2. “The consumer is exhausted. There is rising credit card debt.”

Certainly, the latest Fed study of household finances shows that Americans outside the wealthiest 20% have run out of extra savings and now have less cash on hand than they did when the pandemic began. For the bottom 80% of households by income, bank deposits and other liquid assets were lower in June this year than in March 2020, after adjustment for inflation.

Even so, a recession, according to Tikehau’s Thuin, is still on the table as the lagged effects of the Fed’s aggressive monetary tightening finally trickle in. “The estimate is 12 to 24 months,” he said, referring to how long it usually takes for the rate hikes to hit the economy; the Fed started to raise the fed funds rate 18 months ago. “It’s exactly now. We are starting to see some effects.”

To Stuart Kaiser, Citigroup head of US equity trading strategy, the earnings season is more of a “wildcard.” He said he expects a repeat of the second quarter, which was “neutral at best for equities given a higher bar. The positive case would be companies follow the Fed and revise up 2024 numbers that have proved too conservative,” he added. “The negative case revolves around margin pressure as the revenue growth from higher prices is no longer able to offset -nput and labor costs.”

Nicholas Colas, co-founder at DataTrek Research, also doubts the upcoming earnings season can provide much of a catalyst for stocks. He points out that 69% of S&P 500 tech companies have given guidance, compared to just 16% of non-tech companies. “When management puts their reputation on the line with markets by projecting future earnings, it gives investors incremental comfort that they will not be disappointed when numbers are released,” Colas said. “This both dampens stock price volatility and increases valuations.”

Or put differently, the positive momentum largely comes from tech, and it’s already in the price. Now let's see if other companies, many of them much more cyclical, can deliver a surprise, and hope that it’s a positive one.

3분기 실적 시즌에는 기술주보다 그 외의 경기 민감주에 주목할 필요

— Isabelle Lee

French Zouaves in the woods of Caures at the Battle of Verdun, 1916.Photographer: De Agostini Picture Library/Getty

What Is “Ils Ne Passeront Pas” in Japanese?

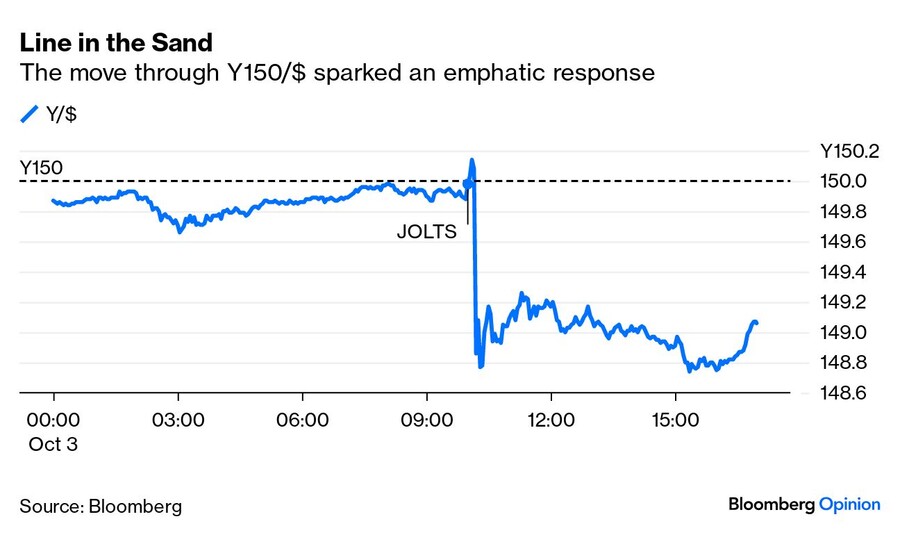

Whatever happens to rates elsewhere, currency traders must now be clear about one thing. They can weaken the yen as much as they like, just as long as they don’t take it beyond Y150/$. That is the line they cannot cross, at which point there will be intervention. Witness Tuesday’s events.

Surging bond yields in the US tend to attract money to the dollar, and away from the yen. Tuesday morning brought the JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) for August, which showed a sharp increase in vacancies. That implied more wage pressure, and a greater need for the Fed to push up rates yet further. As Jonathan Levin of Bloomberg Opinion explains here, it’s highly questionable that the JOLTS, a fallible survey, was really that surprising; it was sharply above expectations but bang in line with the six-month average, and more or less exactly where economists had projected for July — adding up to the steady and slow weakening of the jobs market that the Fed is trying to engineer. There are also tricky seasonal adjustments as August sees lots of job ads for teachers in the run-up to the new school year:

In the current febrile environment, traders only needed an excuse, rather than a copper-bottomed reason, to drive yields further. That in turn pushed the US currency up against the yen, to the level of Y150 per dollar.

At the time of writing, there has been no formal confirmation that the Japanese authorities intervened, but it’s a little obvious. The official comment, from Vice Finance Minister Masato Kanda, was: “I refrain from commenting on whether there has been foreign exchange intervention. We will continue with the existing stance on our response to excessive currency moves.”

And to some extent, it doesn’t matter. To quote Bloomberg Markets Live strategist Mark Cranfield:

"Whether or not Tuesday’s sudden drop for USD/JPY turns out to be official intervention, traders will see it as being ineffective. In October 2022 it took an overwhelming amount of force from Japanese authorities to turn the yen stronger, along with an initial move lower in US yields. Neither have arrived yet, which suggests aggressive traders will stick with yen shorts."

Further, whatever happened at Y150 had nothing to do with split-second human judgment. The instantaneous reaction once the Y150 level broke suggests that this was a mechanistic response that had been programmed long in advance. The other circumstances didn’t seem to matter; Japan has decided it’s not prepared to let the yen get that weak. Moreover, the round number matters, but not much more than that; there's a floor under the yen, but it still ended the day above Y149, which is historically extreme. The history of foreign exchange is littered with governments attempting to hold a line, only to discover that currency speculators lap up the opportunity to bet against a fixed target.

Axel Merk of Merk Investments, a long-time advocate of hard money assets, asked if this was even intervention “when the buy program was set up months ago and forgotten.” He added: “Currency intervention merely puts a currency on sale, giving speculators an opportunity to make more money. Not giving investment advice, but interventions serve few purposes other than to discourage leverage.”

Holding the line, but at what cost? Ruins of Fort Troyon, which prevented German troops encircling Verdun from the south.Photographer: Sean Gallup/Getty

Is there anything better to be said for such a strategy? “Ils ne passeront pas” (“They shall not pass”) entered the global vocabulary after the Battle of Verdun (베르됭 전투, 인류 역사상 가장 참혹한 소모전) in 1916, when the French leadership used it as a slogan to goad their troops into ever greater efforts to repulse a German offensive. In this they were successful. After the longest battle of the war, Germany gave up its attempt to take the city late in that year. But Verdun has not gone down in history as a glorious victory for France. Rather, it’s regarded as one of the greatest and most pointless wastes of human life ever. The French held the line but made no great advance.

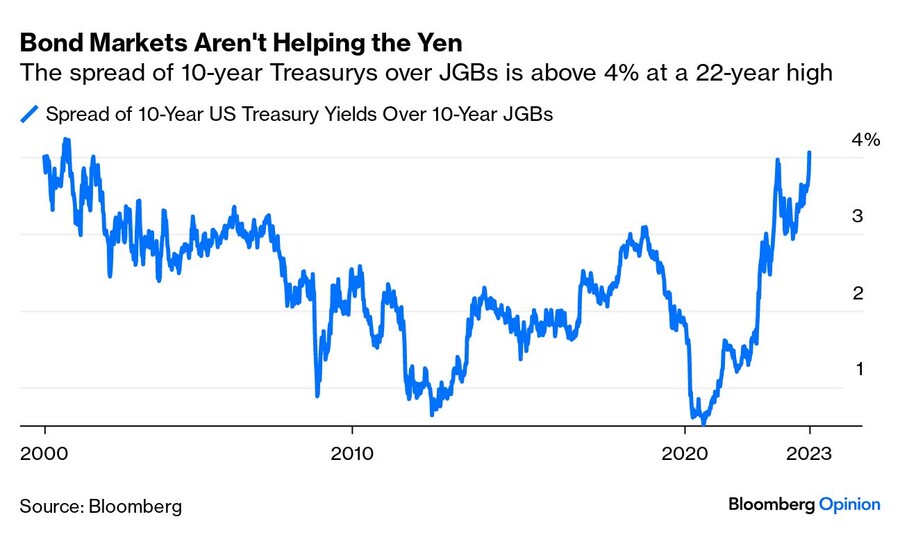

Thankfully no blood is shed in the foreign exchange market. Beyond that, the similarity seems strong. Like the French at Verdun, Japan’s Ministry of Finance has drawn a line at Y150, and won’t let traders cross it. But there’s no great attempt to move the yen further. And the Bank of Japan is still buying more bonds in an attempt to keep their yields down, in a move that directly undercuts attempts to defend the currency. With the 10-year Treasury now yielding 4.84% while the BOJ limits the equivalent Japanese government bond to 0.75%, the spread between them now tops 4% for the first time in 22 years.

None of this stops rampant betting in the futures markets that the BOJ will soon have to give up on Yield Curve Control (which would help the yen and likely drive one last leg in the yield spike elsewhere). And as Japanese stocks like a weak yen and hate higher yields, the effect on the recently resurgent stock market is also sadly predictable. The selloff in Tokyo during morning trading leaves the Topix index down 8.6% from its peak on Sept. 15 — or 9.5% in dollar terms.

Like the French at Verdun, Japan might be able to hold a line for the yen, but their overall strategy seems to ensure they will gain little benefit from doing so. That leaves them with a weak currency, and a great opportunity for currency speculators.