Authority Vs. Freedom, Markets Edition

권위주의 국가에 대한 투자는 타당한가?

독재 국가는 투자자를 정부의 간섭에서 보호해 주는 법치주의가 약하기 때문에 민주 국가에 비해 뒤쳐지는 것은 당연

하지만 반례도 존재

스페인의 프랑코 독재 정권은 당시 선진국 시장을 능가하는 주식 시장 수익률을 기록했음

독재 정권이지만 자원이 풍부한 국가들이 많음 (자원의 저주)

이런 독재 국가들은 (중국발) 원자재 호황이었던 2000년대 중반에 특히 강세를 보였음

새로운 원자재 슈퍼 사이클이 시작된다면 이런 국가에도 투자해야 할 것

ESG 투자가 유행하면서 기관 투자자들은 독재 국가에 대한 투자를 꺼리게 됨

그러면 이들 국가의 자산 가격이 저렴해져 투자 매력이 높아질 수 있음

윤리적 투자자가 담배나 주류 관련 종목을 포트폴리오에서 제외하자 다른 투자자들이 저렴하게 매수할 수 있었던 것과 마찬가지

Unyielding Higher Yields

이스라엘-하마스 분쟁으로 인해 안전 자산 선호 현상이 발생했고 이에 10년물 국채 금리가 하락

그러나 사건이 발생한지 거의 1주일만에 국채 금리는 낙폭을 모두 되돌리며 반등

국채 금리가 왜 이렇게 많이 오르는가?

그럼에도 주식 투자자들이 차분한 이유는 무엇인가?

Pesky US Consumers

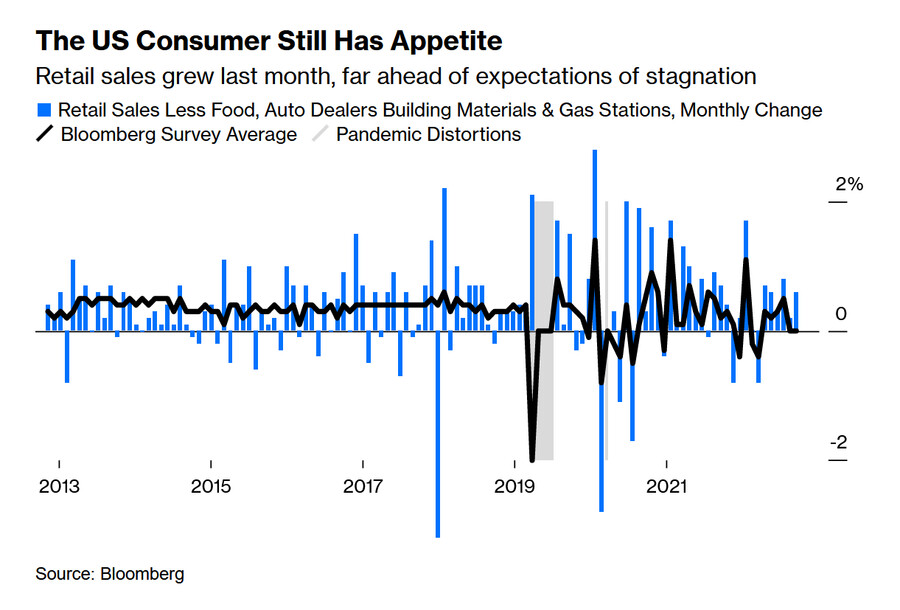

9월 미국 소매 판매는 예상치보다 크게 높았음

근원 소매 판매는 전월 대비 0.6% 증가했는데 예상치는 0.1%에 불과

연준은 미국 가계의 초과 저축이 지난 1분기에 소진됐을 것으로 추정했음

그러나 강력한 소매 판매 데이터는 잉여 저축이 여전히 존재함을 시사

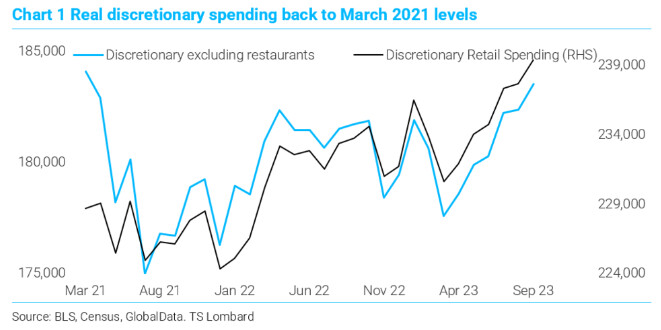

외식을 제외한 임의 소비가 2021년 3월 수준으로 늘어난 것을 생각하면 이는 놀라운 일임

The Fed

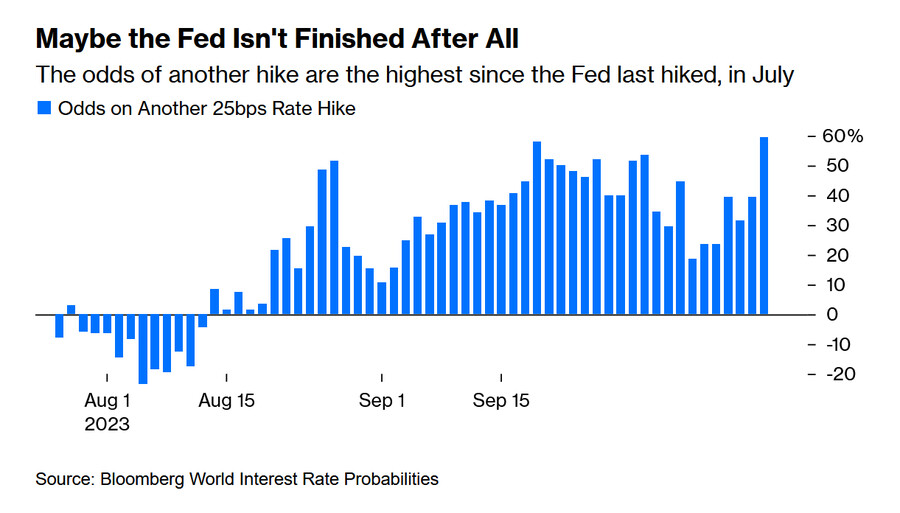

이에 연준이 기준 금리를 추가 인상할 것이라는 믿음이 강해졌음

연준이 내년 1월까지 기준 금리를 한 번 이상 인상할 확률은, 연준이 금리를 동결했던 지난 7월 이후 가장 높은 수준

The Bond Vigilantes

미국의 대규모 재정 적자로 인해 투자자들이 더 높은 금리를 요구하고 있음

물론 미국이 달러를 찍어내면 국채 부도는 없겠지만, 그 결과 인플레가 심해질 것이기 때문에, 투자자들은 더 높은 금리를 요구

연준의 양적 긴축, 일본의 YCC 정책 폐기 움직임, 중국이 주도하는 BRICS국가의 달러 대비 자국 통화 방어 시도로 인해 국채 수요 감소

그래서 경기 둔화, 인플레 완화, 연준 금리 인상 중단에도 국채 금리는 계속 상승할 가능성

And Finally, Why Can Stocks Deal With This?

채권 금리가 5%에 달하고 있으며, 이는 다른 자산들의 가치가 재평가되어야 한다는 의미

그래도 주식 시장이 태연한 이유는?

매그니피센트7을 제외한 나머지 종목들은 거의 오르지 않았음

주식 시장은 경기침체가 시작된 후에 바닥을 찍는 경향

즉 주식 시장은 다가오는 위험을 예측하는 것에는 능숙하지 않음

하지만 경기 회복을 예측하는 것에는 탁월함

주가는 경기 회복 이전에 반등하는 경향

따라서, 노동 시장 약세가 분명해질 때까지 주식 시장 강세는 지속될 것

연준 인사들은 채권 금리 상승으로 인해 기준 금리 추가 인상 필요성이 줄어들고 있다고 발언

이런 비둘기파적 발언도 주식 시장에 도움이 됐을 것

기준 금리 인상 종료 베팅은 위험하지만, 적어도 당분간 주식 시장은 이에 만족할 것

The Sun Also Rises in Japan

엔화가 약세를 보이면서, 달러/엔 환율이 150선에 근접

이는 이번 달 초 일본 은행이 개입했던 수준

향후 일본 은행의 정책, 일본 국채 금리, 엔화에 대한 블룸버그 설문조사(MLIV 펄스 서베이)가 진행 중

===============================================

If you exclude commodities and the ‘resources curse,’ then the returns from free and democratic economies easily beat authoritarian systems.

By John Authers

John Authers is a senior editor for markets and Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A former chief markets commentator at the Financial Times, he is author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets.”

2023년 10월 18일 오후 2:23 GMT+9

Plato has a word with Aristotle in Raphael’s “The School of Athens.”

Photographer: Franco Origlia/Getty

Authority Vs. Freedom, Markets Edition

The debate between the notions of freedom and democracy on one side, against order and authority on the other, has been going on at least since Ancient Greece. Plato didn’t manage to resolve the discussion, and neither will anyone in our lifetime — although the pendulum has certainly swung a long way toward democracy over the last two-and-a-half millennia.

Now comes the fascinating question of how to apply the issue to markets. This is a modern dilemma. After the Russian and Chinese revolutions, nobody could invest private capital there, even if they’d wanted to, and until the 1980s what are now known as the emerging markets went by the name of “lesser developed countries,” in which investment was both difficult and unappealing.

Now, with large non-democratic countries offering deep capital markets, and much of the world rethinking its enthusiasm for democracy, the question is more vital. Should we avoid authoritarian countries? Are democracies any better for your money? There’s a moral dimension to this, of course. If you choose to avoid Russian assets out of moral revulsion for Vladimir Putin, that would seem perfectly sensible. But as we know from the debate over environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing, there’s an argument that investors should put such qualms out of their minds when deploying other people’s money, and aim for the best return.

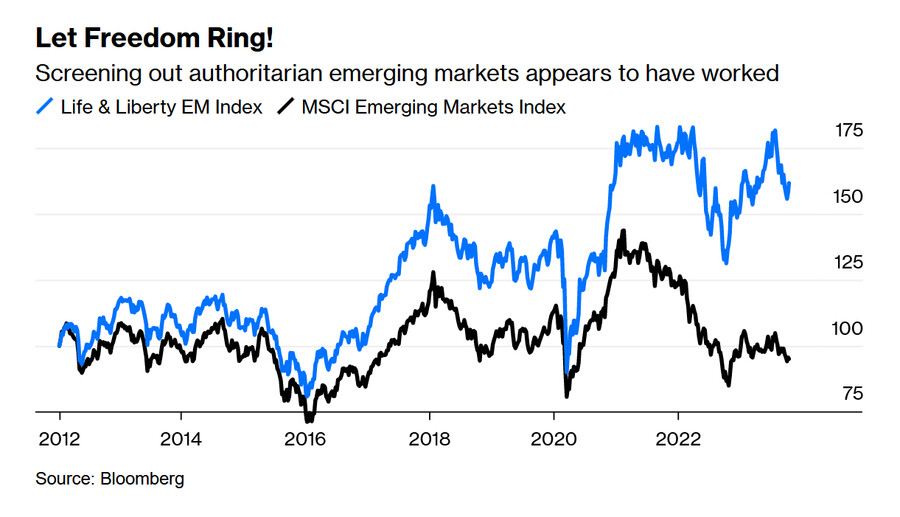

Should you wish to do so, there has since 2012 been a so-called Life & Liberty Emerging Markets Index, administered by the libertarian Cato Institute, which redistributes the different emerging markets according to their score on various measures of openness and democracy. South Korea and Taiwan account for 42% (compared to 27% of the MSCI Emerging Markets, whose history of inclusions and exclusions can be found here). China and India (46% of the MSCI index) are both excluded. The Life & Liberty index also features big weightings for relatively small markets such as Chile (16.4%) and Poland (15.6%). Its performance since inception compared to the full MSCI EM index is remarkably good:

Its success since the end of the brief 2021 boom in Chinese stocks is easily explained; it omitted China completely. That country now accounts for close to a third of the mainstream MSCI index, and its fall from grace was driven in large part by governance issues. If an autocratic Chinese government reserved the right to interfere with the private sector and bully the largest entrepreneurs out of any attempt at opp-osition, that’s plainly a serious problem for external investors. You need a stronger rule of law, with institutions that can protect you against governmental overreach, and they’re not available in a system like Xi Jinping’s China.

Perth Tolle, who manages an exchange-traded fund that tracks the Life & Liberty index, says this is the reason why relatively free countries have performed so well over the last decade. “Freer countries are more sustainable and recover faster... You can see that in the recovery after Covid. They used their capital more efficiently, both human and financial.”

She added that the intensifying geopolitical tension would help, as “the neutral is going to disappear” and countries that have tried to toe a middle line — such as India, whose recent crackdown on free speech means that it narrowly missed inclusion in the Liberty index — would have to decide whether to side with the western concerns (Ukraine and Israel), or with the camps in these conflicts that are backed by autocracies. That should only help the stock market performance of the world’s democracies.

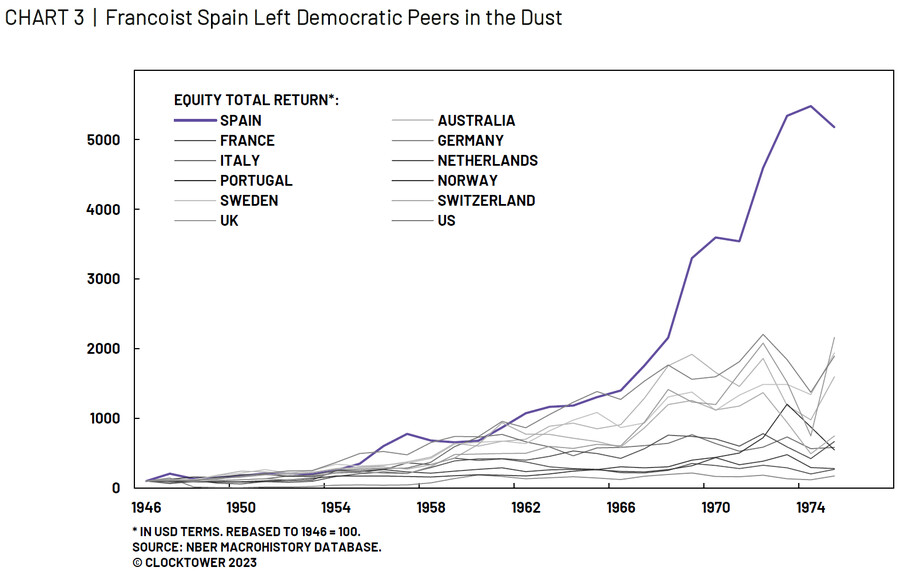

But how far can we take this? There are counterexamples of authoritarian governments delivering good results for investors. Perhaps most startlingly, the government of Francisco Franco in Spain, one of the nastiest and also ineffective dictatorial regimes in recent history, oversaw stock market returns far superior to the developed markets of the time. The chart is from Marko Papic of Clocktower Goup:

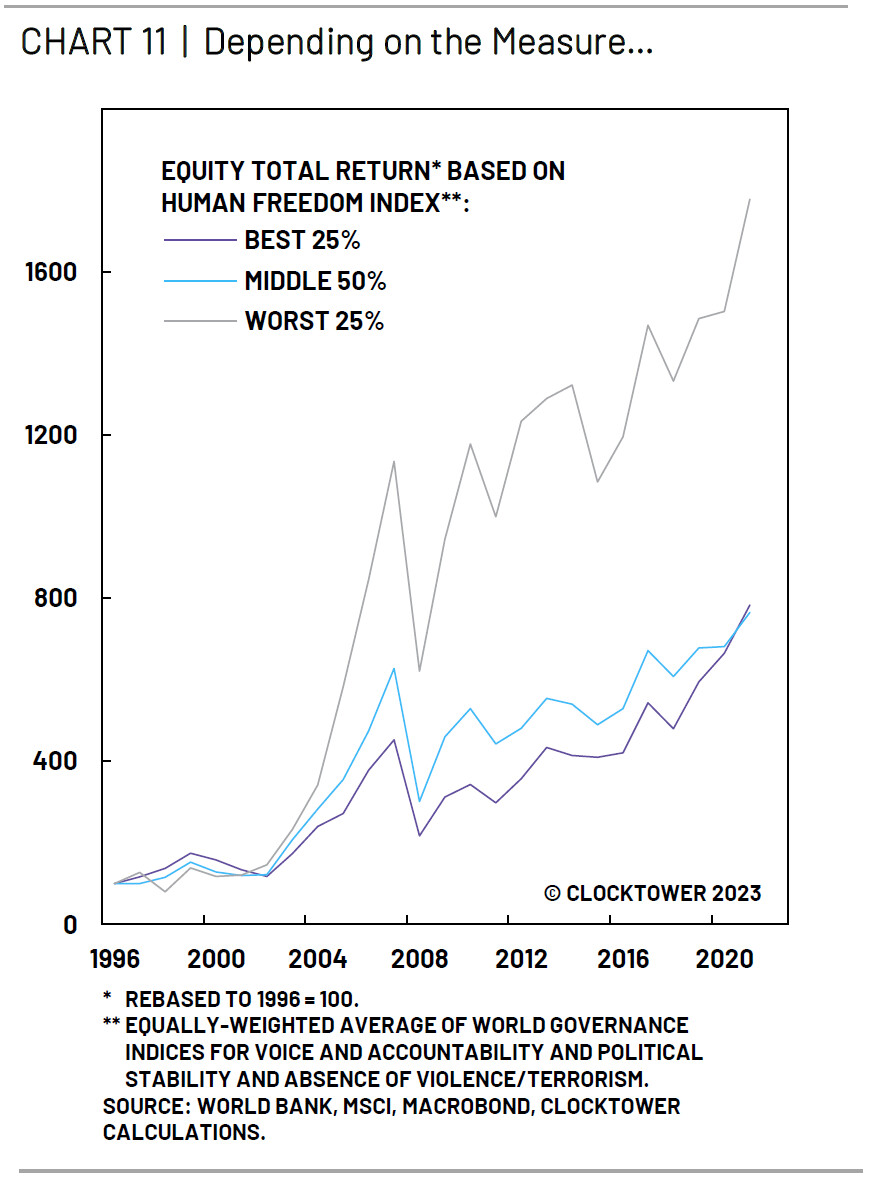

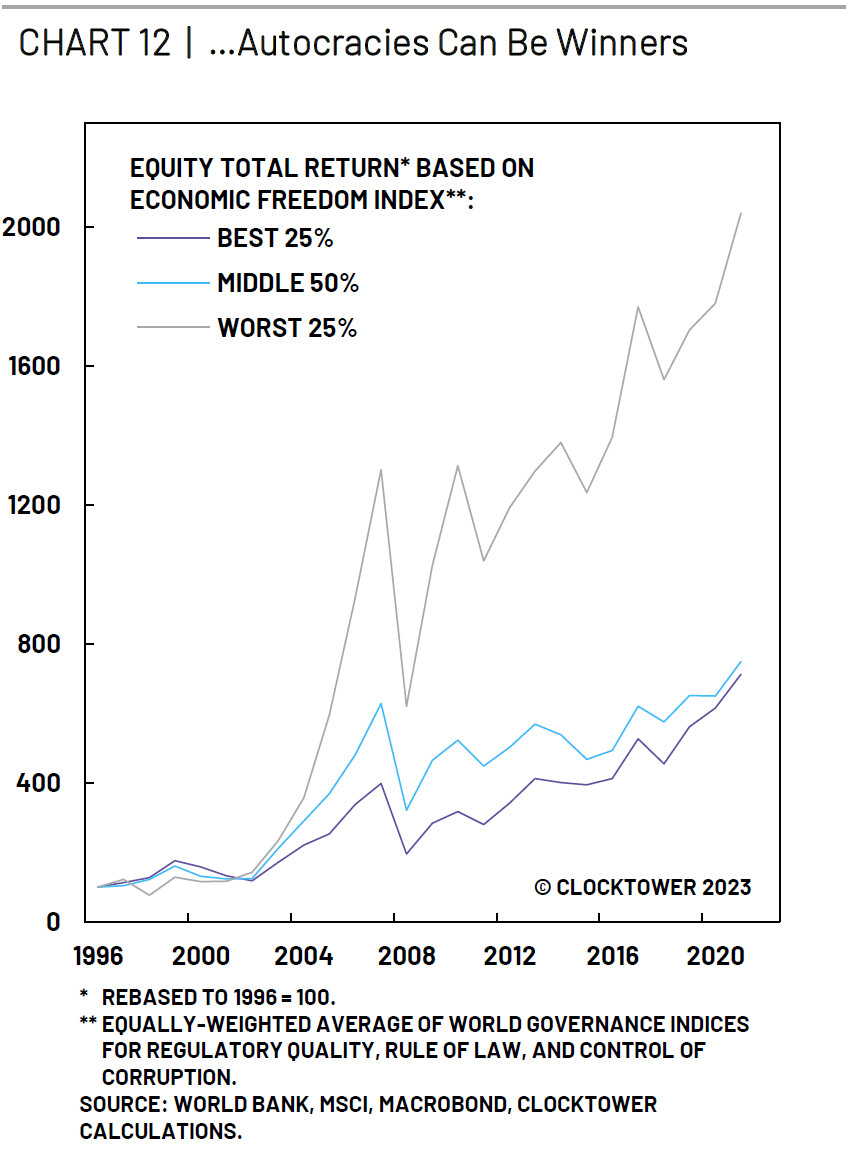

According to Clocktower, it might pay off to be a bit more Machiavellian. Using the World Governance Indices produced for the World Bank, which rank countries by different metrics, Papic shows that the worst countries according to both human freedoms (low crime and political stability) and even economic freedoms (to do with the strength of institutions and the rule of law), have beaten everyone else since 1996:

Why is this? Papic’s case for autocracies ceners on commodities. Most authoritarian regimes control a lot of them, which is probably not a coincidence. The “resources curse” makes it easier for despotic rulers to hold on to power, and also acts as a disincentive to the hard decisions that can drive greater growth. Countries like South Korea and Taiwan, neither of which benefits from any great supplies of commodities, have grown as they have in part because this lack forced their rulers to be more innovative and competitive — and even, arguably, to adopt democracy over time. Meanwhile, the un-free countries in the above charts logged their great period of outperformance in the middle of the 2000s, when commodity prices were in a historic bull market.

Photographer: Jerome Delay/AFP/Getty

That suggests to Papic that there’s a case for authoritarian governments; or at least for not being put off commodity producers by loathsome governments if the commodity cycle is cranking upward again. A further reason why he suggests authoritarian countries might do well in future is that ESG investing (along with government restrictions on the likes of Russia and China that have made many investors leery of putting money there) has made them too cheap:

"The ESG revolution has steered many of our institutional clients away from the economies that are most likely to profit from the capex cycle and the subsequent commodity revolution. This herding effect will mean that many funds will underperform as they plough into normative investment decisions, while steering clear of the biggest winners of this cycle."

In much the same way that the growth of ethical investors who excluded tobacco and alcohol from their portfolios created opportunities for less scrupulous buyers to pick up bargains, it’s possible that autocracies are being driven down to a point where they become compellingly cheap. An easing of global tensions — thereby easing trade issues — and a rally in commodity prices might well help more authoritarian economies. But over the last decade, for all the pain it inflicted along the way, it’s good to know that it was the good guys, armed with liberty, who performed best.

Unyielding Higher Yields

It takes more than a terrifying atrocity followed by the real risk of an escalating land war in the Middle East to put off the bond market. By mid-session on Tuesday, 10-year Treasury yields were back up above their level on the eve of the Hamas attacks. The buying that followed the increase in geopolitical risk had been completely counterbalanced after barely a week of trading. (The bombing of the hospital in Gaza, a tragedy that also makes escalating war look more likely, happened after New York trading, but early indications from Asia are that even this has not prompted a major rush to the shelter of bonds.)

Meanwhile, there was an easy way to dodge the losses in bonds; sell them short relative to stocks. The outperformance of Bloomberg’s index of 20+-year Treasury bonds by the S&P 500 has continued almost uninterrupted since the pandemic summer of 2020:

The trend continued Tuesday, with stocks wobbling between small gains and small losses all day as bond prices plummeted. So, why are bond yields rising so much, and how can equity investors be so calm about it?

Pesky US Consumers

Americans were supposed to be running out of spending money by now. It looks as though they aren’t. The proximate cause of the day’s surge in bond yields was a retail sales report for last month that came in far stronger than almost anyone had expected. Core retail sales rose 0.6% on the month, against an expectation of 0.1%, for the biggest surprise of the year. Some of the extreme months of the pandemic have been excluded from the following chart for legibility:

It looks very much as though there are still more excess savings in circulation, despite research from the Fed that suggested they had run out after the first quarter. That’s hard to believe now that discretionary spending excluding restaurants (a category born during the pandemic) is back to its level of March 2021, the last time “helicopter money” stimulus was distributed. This chart is from Steven Blitz of GlobalData TS Lombard:

The Fed

The issue has reverted in recent months from where rates would peak, to how long they stay high. After zero interest rates throughout 2021 proved to be critical in allowing consumers and business to lock in long-term cheap finance, the lesson has now been learned that keeping rates high for longer might be just as tightening as a higher peak with a quicker descent.

Meanwhile, the retail sales numbers have revived belief that the Fed may yet have to hike again, having deferred on doing so since its July meeting. The following chart shows how the implicit probability of at least one more hike by next January’s meeting has moved since then. The odds of such a thing are now the highest since July.

Note that this cannot explain the ramp-up in yields since the summer. But if you want to explain how bond yields have clambered close to their high again, the rising possibility of another hike is it.

The Bond Vigilantes

The abiding fear for years has been that investors will revolt against the huge weight of debt that the US government has taken on, and demand a higher yield. This isn’t strictly speaking about the risk of default; the US can print its own money, so it can always repay its dollar-denominated debts. What is much more likely is that such an attitude to money creation would drive higher inflation, forcing investors to demand a higher yield from bonds as protection.

Or, put slightly differently, is there a risk of a “buyers’ strike” for whatever reason? Steve Chiavarone, head of multi-asset solutions at Federated Hermes, points out that the biggest buyer of recent years (the Fed) is no longer buying. The biggest foreign buyer, Japan, whose purchases of Japanese government bonds under so-called yield curve control have created cash that finds its way to US bonds, is readying to move away from the policy. The BRICS nations, led by China, are also reducing their Treasury holdings, possibly to manage their currencies against the strong dollar. Chiavarone suggests this is a “less benign” explanation, because “it could suggest that yields continue to move higher or stay elevated, even if inflation eases, the Fed pauses and the economy slows. In other words, the bond market could tighten even if the Fed stops.”

Who is doing the work on tightening now?

Photographer: Samuel Corum/Bloomberg

And Finally, Why Can Stocks Deal With This?

Steve Sosnick, chief strategist at Interactive Brokers, states the issue succinctly: “For how long did we hear about TINA, there is no alternative? Guess what, there IS an alternative, and that’s a 5% risk-free rate. That means that all assets need to be repriced.”

So how come stocks can deal with the sudden rise of a powerful competitor with such stoicism? As is often the case these days, the overall indexes might be deceiving. Lauren Goodwin, economist and portfolio strategist at New York Life Investments, suggested the odd and top-heavy performance of US stocks this year had much to do with it:

"The equity market minus the Magnificent Seven is flatter, a little down. We’ve seen earnings expectations revised down, especially for cyclical companies. And so there is uncertainty and some acknowledgement of the upcoming risk. And equity markets don’t tend to really churn until we are already in recession."

Generally, equity markets are not great at spotting trouble coming, and don’t hit bottom until a recession has already started (one of the strongest arguments against the claim that US stocks are in a bull market at present), but are pretty good at pricing or anticipating a recovery, normally turning upward before the economy does. That adds up to continuing strength for equities, which Goodwin suggests can continue until the labor market starts to show a clear deterioration.

Tom Hainlin, national investment strategist at US Bank Wealth Management, adds that “Fedspeak” in the last week has helped avert a major selloff in stocks. The clear messaging of late that higher bond yields are doing the central bank’s work for it tends to imply that there’ll be no need to raise short-term rates any further and we’re “perhaps closer to their eventual shift to cutting rates maybe later in 2024 or 2025.” It’s a dangerous bet on the Fed, but for now stock investors seem happy with it.

—Reporting by Isabelle Lee

The Sun Also Rises in Japan

The Japanese yen is weakening again, and now very close to the Y150/$ level that prompted a government intervention earlier this month. The pressure from high Treasury yields is not abating:

So what happens next, as both the Finance Ministry and the Bank of Japan contemplate difficult questions, and what effect could this have on markets in Europe and North America? You now have the chance to answer those questions in an anonymous MLIV Pulse survey organized by the Markets Live blog on the terminal. The main questions: When will the BOJ give up on a negative policy rate, when will 10-year Japanese government bonds reach their current 1% threshold; where will the USD/JPY exchange rate finish this year; which asset class will suffer the most from rising JGB yields, and what will be the three-month return of the Nikkei index after the BOJ ends negative rates?

The results will be out next week. Please take part if you can.