블룸버그 뉴스 요약

Ker-Powell!

파월 의장의 뉴욕경제클럽 연설

파월 의장은

① 장기 국채 금리 상승이 금융 여건을 긴축시켰고

② 기준 금리 인상이 경제에 미치는 영향에는 시차가 있기에

당분간 (추가 금리 인상 없이) 경제 상황을 지켜보겠다고 말함

그래서 (통화 정책에 민감한) 2년물 금리와 달러는 내렸고, S&P 500은 올랐음

그러나 그 후 시장은 거의 완전히 반대로 움직였음

파월 발언 직전에 발표된 신규 실업급여 청구 건수는 20만 건을 하회하며 노동 시장이 여전히 강하다는 걸 보여줌

파월은 "경제가 지속해서 추세를 넘는 성장세를 보이거나 노동시장이 더 둔화하지 않는다는 추가 증거가 나타나면 인플레이션이 더 진전될 수 있고 통화정책을 더욱 긴축해야 할 수도 있다"고 말했음

파월은 질의 응답 시간에 "현재 통화정책이 너무 엄격하다는 증거는 없다"고 말했음

연준의 긴축 정책이 금융 여건을 긴축시키고 있는지가 매우 중요함

모기지 금리가 8%를 넘었는데 이는 2000년 여름 이후 처음있는 일

2년 전과 비교하면 가계가 주택을 구매하는 것이 매우 어려워졌음

따라서 금융 여건이 충분히 긴축되었다고 볼 수도 있음

하지만 (모기지 금리 같은) 장기 금리가 중요한데, 이는 (단기 금리에 비해) 기준 금리 변화에 훨씬 덜 민감함

장기 금리는 장기적 요소에 의해 움직이며, 장기 금리가 오를 이유는 충분함

→ 재정 적자 심화, 연준의 양적 긴축(QT) 등

문제는 시장의 생각과는 달리, 파월은 장기 금리 상승에 대해 매우 편안하게 생각하는 것 같았다는 점

그는 정책 결정권자들이 장기 금리 상승을 지켜보며 무슨 일이 일어나는지 지켜볼 것이라고 말했음

연준이 금융 시스템에서 무언가 부러질 수 있다고 걱정했다면 이는 채권 매수 신호가 됐을 것이고 금리도 떨어졌을 것

하지만 파월은 그런 신호를 보내지 않았기에 결국 국채 금리는 더 올랐음

채권 트레이더들은 추가 기준 금리 인상은 없다고 보지만, 장기 금리 하락에 대해서는 확신이 없음

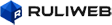

이는 역전되었던 수익률 곡선이 다시 정상화되고 있는 것을 보면 알 수 있음

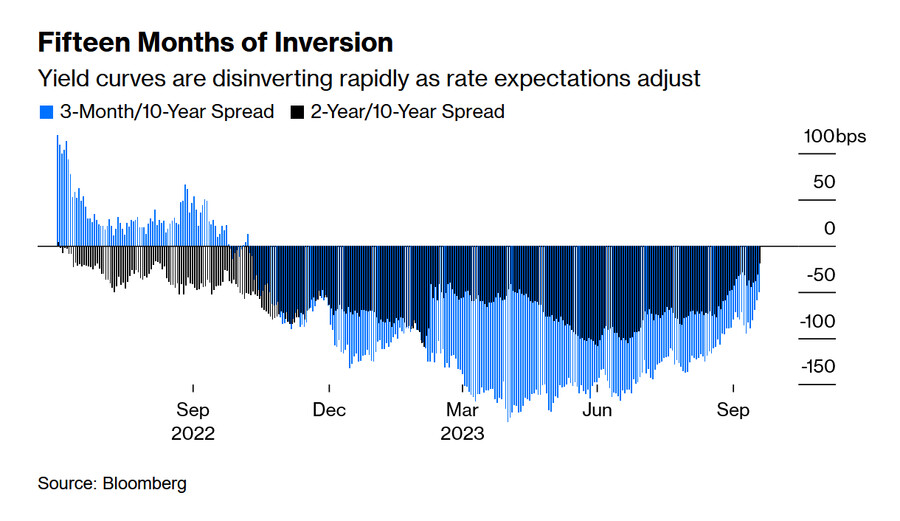

시장이 생각하는 미래 인플레 기대치(Breakeven)가 최근 다시 올라가고 있다는 것도 부담

인플레이션이 꺾였다는 시장의 자신감이 흔들리기 시작했을 수 있음

파월은 연준이 단일 기준이 아닌 광범위한 금융 여건을 고려한다고 말해왔음

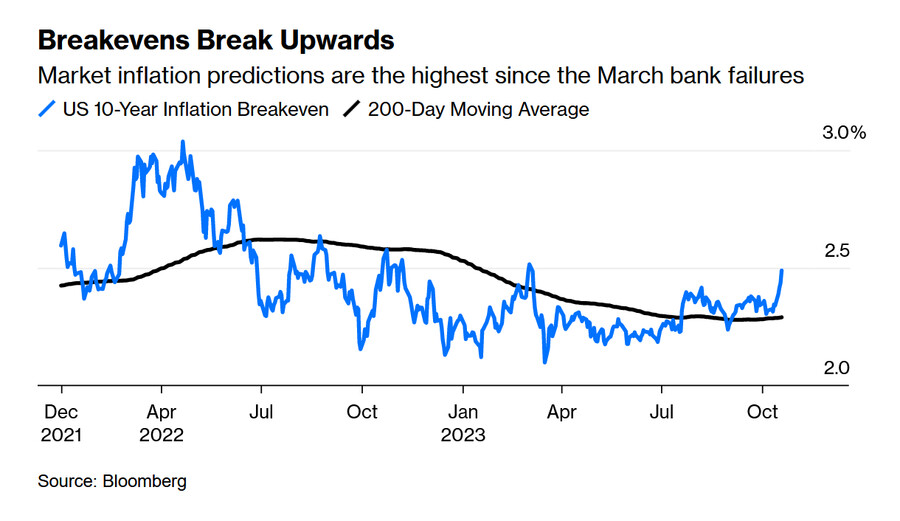

그런데, 연준이 선호하는 (광범위한) 시카고 연은 금융 여건 지수는 (이번 금리 인상 이후 가장) 완화적

투자자들은 연준이 국채 금리 상승에 대해 별로 걱정하지 않는 것을 우려하고 있음

앞으로 어떻게 하겠다는 구체적인 메뉴얼이 연준에게 없다는 것

물론 팬데믹 이후의 상황은 전례가 드문 일이기에 메뉴얼이 없는 건 당연한 일

투자자들은 이런 상황을 불편해 하기 때문에, 파월의 연설 당일 주식과 채권 모두 하락

Meanwhile, Out in the World…

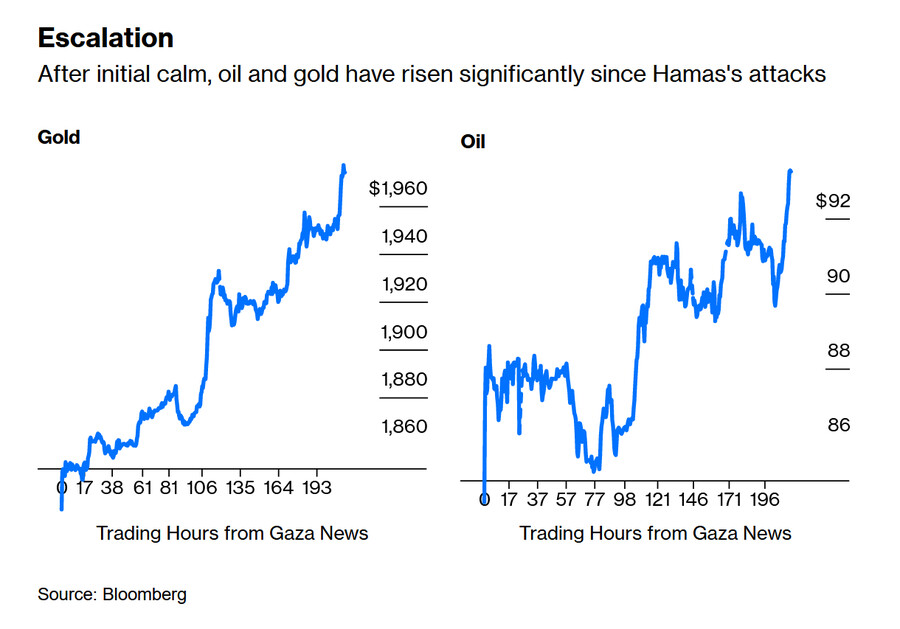

중동발 암울한 뉴스에 유가는 2% 이상 상승, 금도 온스 당 2,000달러에 가까워졌음

원유와 금은 중동 지역 정세에 가장 민감한 자산으로, 하마스-이스라엘 분쟁으로 약 5,000명의 사상자가 발생하면서 상승했음

사태 발생 초기에 시장은 이번 분쟁이 국지전에 그칠 것으로 봤지만 이제 그런 전망은 약화되고 있음

중동 분쟁이 확산될 우려가 커지자 미국은 베네수엘라 원유 수출 제재 완화에 나섰음

그러나 베네수엘라는 의미있는 수준으로 증산하지 못 할 것이기 때문에, 이로 인한 유가 하락은 일시적일 것

유가와 금은 안전 자산의 역할을 했지만, 금리에 대한 불확실성 때문에 채권은 안전자산 역할을 하지 못했음

지정학적 긴장이 고조되면 투자자들은 채권과 엔화를 안전 자산으로 여겼지만 이번은 그렇지 않았음

금융 시장에서 (재정 적자 우려로 인한) 장기 금리의 불확실성은 중동에서 들려오는 끔찍한 뉴스의 영향력을 능가하고 있음

==============================================

The Fed will clearly be going the distance on higher rates for longer, but traders look like they’ve taken at least some charge of financial conditions.

By John Authers and Isabelle Lee

Hanging on Jerome Powell’s every word at the Economic Club of New York.

Photographer: Bloomberg

Ker-Powell!

Every speech, every utterance by the Federal Reserve’s Jerome Powell is for high stakes. Investors meticulously digest every word he says — with real money on the table reacting in real time.

Thursday was no different. At the Economic Club of New York, the Fed chair sat down for a fireside chat with Bloomberg’s David Westin, the host of Wall Street Week, and suggested that the US central bank is inclined to hold interest rates steady yet again at its next meeting at the end of this month. He’s leaving the possibility of another hike open in case of further signs of resilient economic growth, but as it stands it looks very likely that Powell and his colleagues will skip hiking rates for two consecutive meetings, for the first time in their 19-month tightening campaign.

“Given the uncertainties and risks, and how far we have come, the committee is proceeding carefully,” Powell said in prepared remarks. “We will make decisions about the extent of additional policy firming and how long policy will remain restrictive based on the totality of the incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks.”

So he’s certainly not hinting at easier conditions any time soon. Indeed, JPMorgan’s Michael Feroli went so far as to say that Powell had “sealed the case for no move at the November meeting, while keeping the option alive for hiking at subsequent meetings.” But he did very directly admit that the Fed and the bond markets are now in a state of interdependence, and put a perhaps dangerous amount of faith in bond traders to do the Fed’s work.

Powell was briefly escorted out due to an interruption by climate protesters.

Photographer: Bess Adler/Bloomberg

The key words to latch on to were that “persistent changes in financial conditions” — as has just been witnessed by the surge in longer bond yields — “can have implications for the path of monetary policy.” In other words, higher yields make it easier for the Fed to avoid making further hikes in overnight rates.

Crucially, he also dwelled on the possibility that monetary policy operates with a long lag — a phrase that comes from Milton Friedman, and refers to the way interest rates tend to take a year or more to have an effect on the economy. “Given the fast pace of the tightening,” he said, “there may still be meaningful tightening in the pipeline.”

Powell continued: “There’s no precision in our understanding of how long lags are,” adding that it’s been a year now since the last 75 basis-point hike, which was in November. “So we should be seeing the effects... By the way, they don’t just all arrive on one day.”

All of this was taken as a broad hint that the Fed wouldn’t need to hike rates again, because the bond market was doing the work. Therefore, yields on two-year Treasuries — more sensitive to imminent Fed moves — declined after Powell spoke, while the dollar fell, and the S&P 500 rose. Now, traders see less than a 50% chance that the central bank lifts rates one more time. Read our live blog here.

However, after another four hectic hours of trading, the market had turned around almost completely. The S&P 500 was down for the day, while the 10-year Treasury yield (shown inverted in the following chart) was again approaching 5% for the first time since 2007:

Why did this happen?

Stubborn Economic Strength

Since the last Federal Open Market Committee meeting, job growth has unexpectedly re-accelerated, retail sales have defied predictions of a slowdown, and varying measures of prices have offered inconsistent signals as to whether inflation is on track to glide down to 2% or not, with the Fed’s favored “supercore” measure actually rising somewhat in September. Shortly before Powell spoke, there was a further astonishing sign that the labor market was surprisingly high as claims for jobless insurance, regarded as the best real-time indicator of trends in layoffs, dropped below 200,000. To get a perspective on this, here is how claims have moved over the last three decades (the massive Covid-driven claims of 2020 and 2021 have been excluded for legibility):

“We are attentive to recent data showing the resilience of economic growth and demand for labor,” Powell said. “Additional evidence of persistently above-trend growth, or that tightness in the labor market is no longer easing, could put further progress on inflation at risk and could warrant further tightening of monetary policy.”

Powell, during the question-and-answer session with Westin, added: “I think the evidence is not that policy is too tight right now.”

Financial Conditions

That leads to the other critical issue of the moment: whether the Fed’s tightening to date is beginning to affect financial conditions. There are many different measures of this, but mortgage rates, central to the housing market, have surged above 8% for the first time since the summer of 2000. Compared to two years ago, the viability of buying a house has been radically changed:

With the most important financial numbers for consumers changing as radically as this, it’s clearly prudent for the Fed to bide its time before hiking further. What it has done so far may well be enough. To Peter Boockvar, author of the Boock Report:

"Jay Powell is putting to bed any chance of a Nov. 1 rate hike. As to not let markets get carried away though, he left the door open for more rate hikes… Short rates are falling as they are likely done, but the rise in long rates is proving again that they are losing their grip on that part of the market."

But it’s longer-term rates (such as for mortgages) that matter more, and those are much less sensitive to any imminent changes in fed funds. They are driven by longer-term factors and, as we’ve seen, traders see ample reason to let yields rise further. “They’re revising their view about the overall strength of the economy and thinking even longer term it may require higher rates,” Powell said when asked why traders were pushing yields higher. “There may be a heightened focus on fiscal deficits. QT [quantitative tightening, or selling bonds to reduce the Fed’s balance sheet] could be part of it.”

Perhaps critically, while Powell seemed to think that higher yields meant there was less need for another hike, he appeared intensely relaxed about the widespread belief that he will need soon to try to push longer-dated yields downward. He gave a number of explanations for the rise, including higher government budget deficits, which he stressed are on an “unsustainable” path. At the margin, higher long-term yields could mean less need for the Fed to hike, but he stressed he wasn’t “blessing” any particular level of longer-term rates. Instead, he said that policymakers would let the rise in yields “play out” and watch what happened.

“It’s appropriate to have a little bit of humility,” Powell said, because few people are confident they understand what is happening.

It looks as though bond traders were hoping for him to be less humble, but to give words that suggested he didn’t want yields to rise any further. Any signal that the Fed is worried that something in the financial system is about to “break” would have been the green light for mass buying of bonds, and a fall in yields. He offered no such signal, and so by the end of the day yields had indeed risen further.

The best way to view this is via the yield curve, the degree to which 10-year yields exceed shorter-dated bonds. The gap between two- and 10-year yields has been constantly inverted since last July — but the curve is now closer to disinverting (meaning that long-term yields could soon be higher than short-term yields, as is usually the case) than it has been in more than a year. That means traders are more confident that there are no hikes in the near future, but also much less confident about more cuts in the longer term:

“Given the uncertainties and risks,” Powell said, the FOMC was proceeding “carefully.” He insisted they would look at the “totality” of the data when making decisions. Also on Thursday, a slew of other Fed speakers spoke on the record, including regional presidents Austan Goolsbee (Chicago), Raphael Bostic (Atlanta), Patrick Harker (Philadelphia) and Lorie Logan (Dallas). None of them significantly contradicted Powell’s message.

Whether he’s really being prudent is another issue. While Powell said correctly that the rise in yields so far has not been primarily about rising inflation expectations, it’s noticeable that bond market inflation breakevens have risen sharply in recent days, and rose again after his comments. It looks as though the market’s confidence that inflation has been beaten might be beginning to shake.

Stephen Stanley of Santander described the Fed as “being willfully dovish at the moment,” and predicted that another hike would be needed by the end of the year. He added, in a note:

"I’m puzzled by the sudden FOMC fascination with 10-year Treasury yields as the be-all, end-all indication of the economic outlook. For years, Chairman Powell has insisted that the Fed looks at financial conditions broadly rather than at a particular single measure. Well, I am sure that it will snug in the coming weeks, but the Chicago Fed Financial Conditions Index, which is just what the Fed says that it likes (a broad index that includes both market measures and other indicators, such as from the Fed’s Senior Loan Officer survey) was, as of the end of last week, at its easiest reading since the FOMC began to raise rates. Yes, you read that right."

Others were alarmed by the apparent ease with which the Fed is facing the rise in yields. “There is no playbook,” Powell noted. “With the benefit of hindsight, could we have done a little bit less and had a little bit of inflation? I guess we could.”

Investors concerned that the strain will make itself felt in the market would evidently be more confident if there was a fixed playbook. But the situation post-Covid lacks good precedents, and so Powell may well be right that there is no set of plays for him to follow. Nobody seems to find that a comforting thought — which is why stocks and bonds both had a bad day.

A rally in New York for the release of hostages in Gaza held by Hamas.

Photographer: Stephanie Keith/Bloomberg

Meanwhile, Out in the World…

Powell and his colleagues were not the only ones driving markets on Thursday. Zooming out, geopolitical risks remain real. News that they appeared to be increasing prompted commodity prices to whipsaw.

Oil extended gains past 2% while gold approached $2,000 an ounce in response to fresh dismal news from the Middle East. The two commodities have been the assets most sensitive to risks of escalation in the region as the war between Hamas and Israel claims close to 5,000 lives. News of drone attacks against US bases in Syria and Iraq, and of a US destroyer in the Red Sea shooting down cruise missiles and drones that had been fired in the direction of Israel by Houthi rebels in Yemen (Pentagon officials said they were still assessing the target), prompted a fresh dose of risk aversion.

It’s noticeable that the initial assessment after the terror attacks of Oct. 7 that “what happens in Israel stays in Israel” is beginning to fray. With an apparent increase in the risk of escalation, gold and oil prices both rose sharply on the latest news.

The ripples from Gaza have now reached Latin America. Contributing to the choppy session in oil was a temporary “Band-Aid” deal that’s intended to bring more Venezuelan crude to the market in the coming months. This, said Ed Moya, senior markets analyst at Oanda, has done little to calm the nerves of investors who are worried about dwindling supplies.

“The risks of a wider war in the Middle East will likely lead to extensive efforts by the West to cover any shortfalls or disruptions of crude outflows,” Moya told colleagues. “Venezuela won’t be able to ramp up output to meaningful levels, so whatever oil-price relief we are seeing should be temporary.”

The US’s suspension of some restrictions on Venezuela (in return for plans for freer elections in the country) may enable the South American nation to pump 200,000 more barrels a day, according to analysts’ estimates. That’s roughly a 25% jump in output.

While oil and gold have offered a haven, however, the uncertainty over the direction of rates has thwarted bonds from playing the same function. Normally after a major political shock, investors treat Treasuries, and also the Japanese yen, as shelters. Not this time:

For financial markets, fear about the unknown future of long-term rates is trumping even the terrifying news from the Middle East.