블룸버그 기사 요약

When the Credit Breaks

신용이 위축되면 경기침체는 물론 심지어 금융위기가 발생할 수도 있음

문제는 소형주에서 신용 위축 신호가 보인다는 것

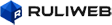

1) 중소형 기업 지수인 러셀2000이 팬데믹 이전 수준으로 하락

→ S&P 500에 속한 대형주들은 팬데믹 이후 저금리 시대에 고정 금리로 대출/회사채 발행

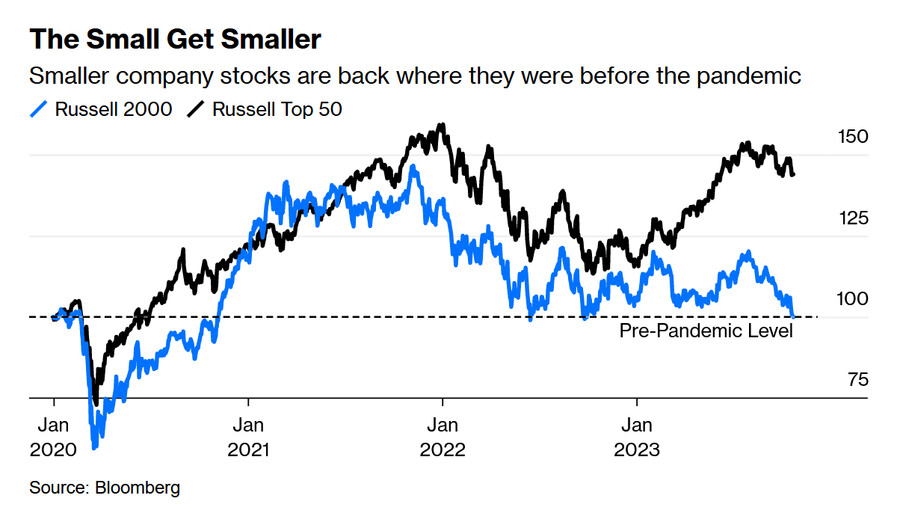

→ 반면, 중소형주들은 주로 단기/변동 금리로 돈을 빌렸으며, 곧 만기의 "벽"을 맞게 됨 (리파이낸싱)

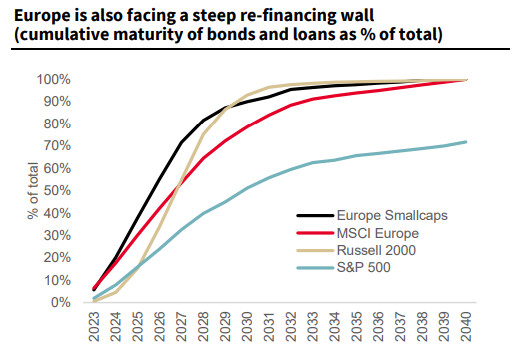

2) 하이일드 스프레드 (중소형 기업 채권 금리 - 국채 금리)도 상승 가능성

→ 하이일드 스프레드는 3월 지역은행 위기 당시 급등 후 하락했으며, 아직 높은 수준은 아님

→ 그러나 최근 200일 이평선을 돌파하며 상승 추세

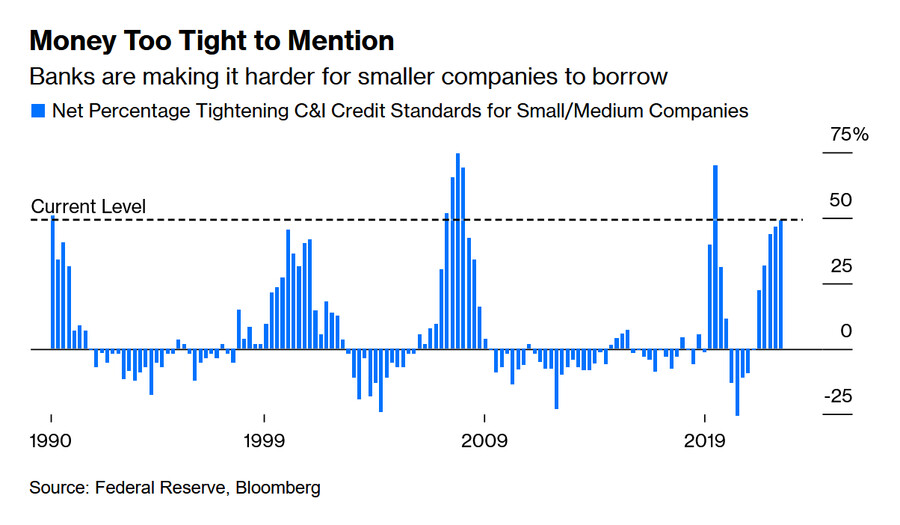

3) 미국 은행들도 중소형 기업에 대한 대출 문턱을 높이고 있음

→ 연준이 조사하는 은행 대출태도 지수는 글로벌 금융 위기, 팬데믹 이후 가장 높은 수준

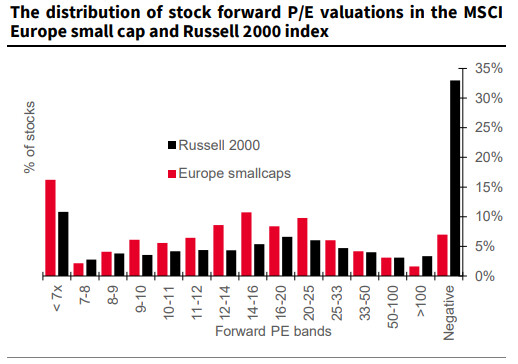

4) 번 돈으로 이자도 못 내는 중소형 기업들은 유럽보다 미국에 더 많음

→ 저금리 시대에는 괜찮았지만 금리가 높아진 지금은 문제가 될 것

→ 이런 좀비 기업에 문제가 발생하면, 미국보다 유럽이 더 나은 상황이 될 수도

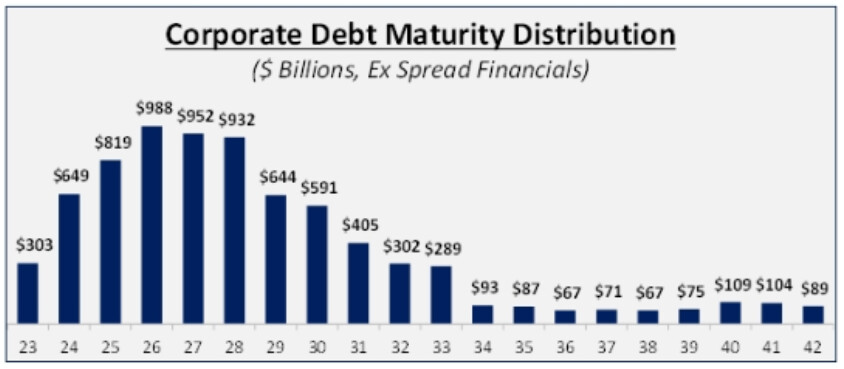

심지어 S&P 500에 속한 대기업들도 부채 부담을 느끼기 시작

→ 대기업들은 팬데믹 이후 저금리로 대출/회사채 발행했지만 이들도 만기를 아주 길게 가져가지는 못 했음

→ 이들도 2025년, 2026년이 되면 갚아야 할 부채가 크게 늘어남

소비자의 소득 대비 부채 이자 상환 비율도 급등

연준의 긴축이 실물 경제에 미치는 시차는 약 18개월

연준은 2022년 3월 이후 금리를 올리기 시작했기 때문에, 이제 그 효과가 나타날 시기가 됐음

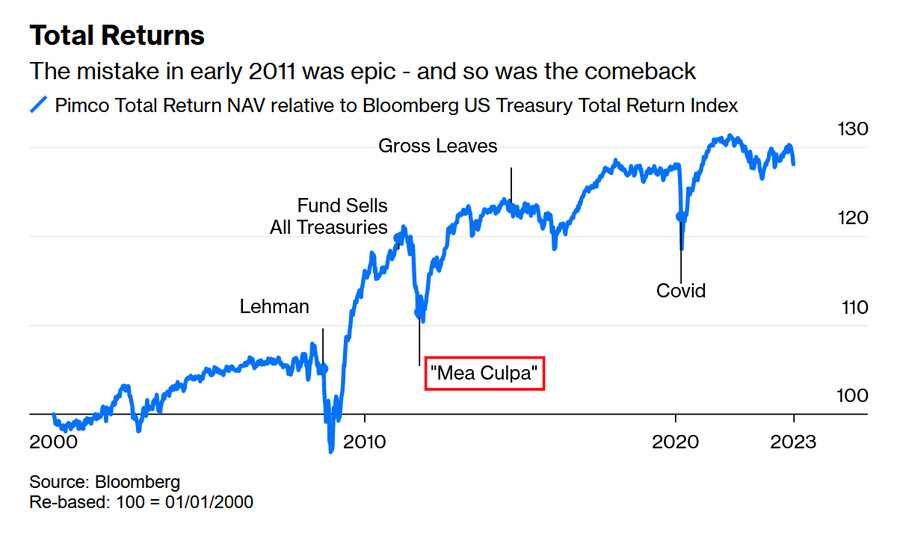

Gross Net Returns

2011년 채권왕 빌그로스는 금융위기 이후 풀린 막대한 돈 때문에 인플레이션이 올 것으로 예상하고 국채를 매도

그러나 인플레는 오지 않았고 국채 가격은 올랐기 때문에 그가 출시했던 채권 상품(Total Return)은 매우 저조한 수익률을 기록

2011년 10월 빌그로스는 투자자에게 자신의 잘못을 인정하는 서한을 보냈음

빌그로스가 자신이 세운 회사를 떠났던 2014년에 Total Return은 2011년의 손실을 모두 회복했음

장기 투자자는 때때로 실수할 수도 있음

중요한 건 실수에 대처하는 방식임

투자자의 중요한 덕목은 정서적 지능임

→ 군중과 반대로 베팅, 손실을 만회할 수 있을 거라는 헛된 희망을 품으면서 잘못된 베팅을 고집하지 않고 실수를 인정하는 것

빌 그로스는 그런 덕목을 갖췄기 때문에 자신의 실수를 만회할 수 있었음

Mr. Xi Visits the Bank

시진핑 중국 국가주석이 취임 후 처음으로 중앙은행인 인민은행을 방문했음

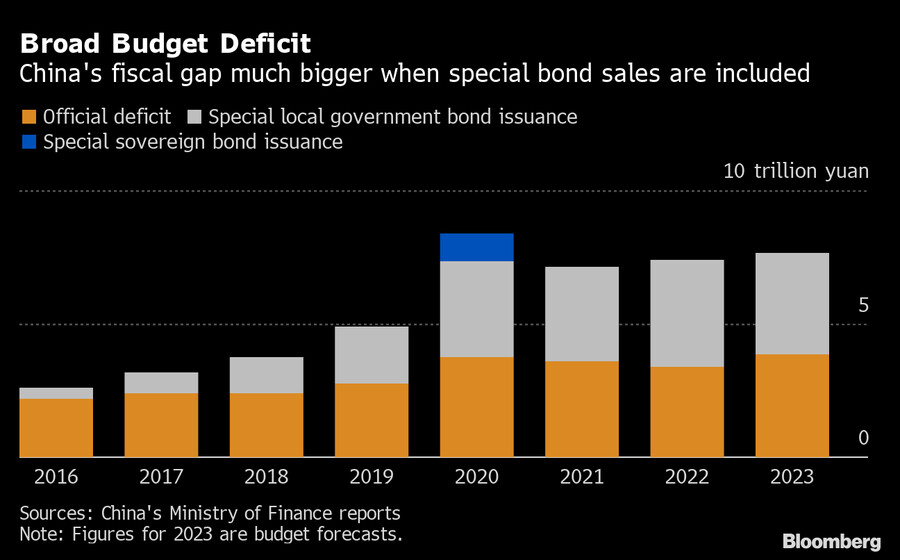

여기에 적자 재정 규모를 국내총생산(GDP)의 3.8%로 확대해 1조위안(약 184조원) 규모의 국채도 추가 발행하기로 함

중국이 연초에 정한 계획을 중간에 변경하는 건 굉장히 드문 일

중국 정부가 부동산 위기 및 디플레 압력에 빠진 경제와 금융 시장을 살리는데 집중하고 있다는 의미

중국 정부가 행동에 나섰다는 건 좋은 소식이지만, 그 정도로 상황이 심각하다는 건 나쁜 소식일 수도 있음

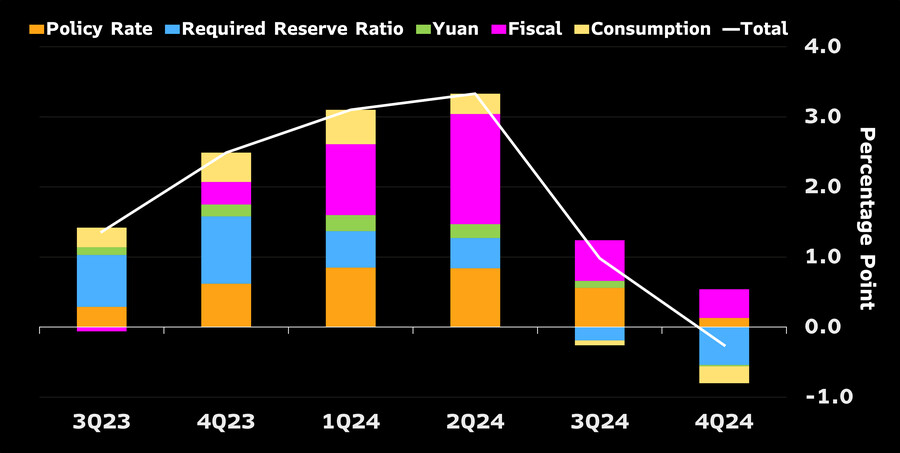

캐피털 이코노믹스에 따르면, 재정 정책은 지난 몇 분기 동안 중국의 경제 성장을 지원했으며, 이번 추가 재정 지원은 이러한 흐름이 끊기지 않도록 하기 위한 것임

시 주석은 외환관리국도 방문했음

블룸버그는 시 주석의 이번 방문이 3조 달러에 달하는 중국의 외환보유액을 더 잘 이해하기 위한 것이라고 말했음

FHN 파이낸셜의 크리스토퍼 로우에 따르면, 이번 방문은 좋은 신호가 아님

중국은 경제를 부양해야 하지만 막대한 부채를 지고 있음

국가 지도자가 외환을 이용해 경기 부양을 시도했을 때, 그 결과는 대부분 좋지 않았음 (예 : 아르헨티나, 브라질)

지난 수십 년 동안 중국의 외환 보유고는 충분했지만, 지금은 자국 통화를 겨우 방어할 수 있는 수준임

이러한 움직임이 투자자에게 가장 직접적 영향을 미치는 건 주식 시장임

중국 주가는 2019년 이후 최저 수준

투자자들은 크게 두 가지를 걱정하고 있음

1) 중국 정부의 부동산 시장 활성화 실패에 따른 신용 위축으로 경제 성장률이 낮아지는 것

2) 기업 실적 악화

중국 정부는 경제에 자신감을 보이지만 시장에는 비관론이 광범위하게 퍼져 있음

이러한 간극의 원인 : 정책 당국은 후행적이며 5% 성장이라는 단기 목표에 집중하고 있지만, 미래를 내다보는 투자자들은 적절한 경기 부양책이 없을 경우, 2024년 이후 저성장이 고착화될 것을 우려하기 때문

Earnings Recap

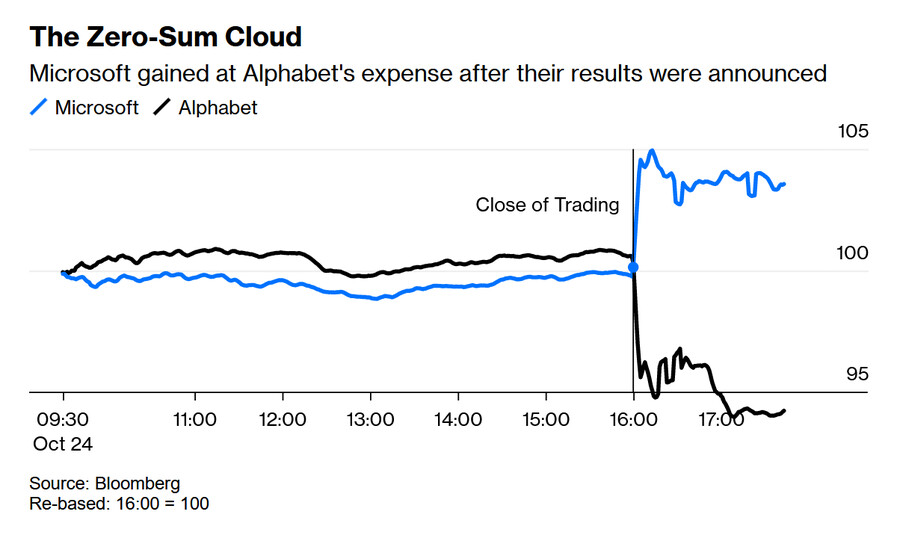

알파벳의 실적은 전반적으로 좋았지만 클라우드 섹터의 어닝 미스로 시간 외 거래에서 급락

반면, 마이크로소프트는 클라우드 사업 호조 덕분에 전망치를 상회하는 분기 실적을 발표했음

마이크로소프트는 시간외 거래에서 5% 가까이 상승

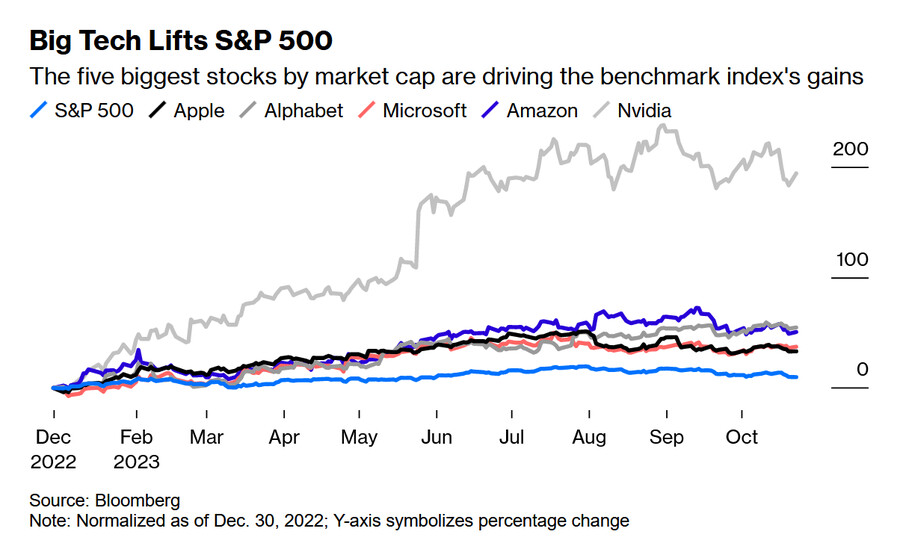

일부 매그니피센트7 기업은 경쟁사를 이겨야 성장할 수 있음

대형 기술주를 평가할 때, 이런 사실을 고려하는 것이 좋을 것

=====================================================

The critical signs coming from small caps are too big to ignore. Plus, the real lesson from Bill Gross that investors need to take on board.

2023년 10월 25일 오후 2:01 GMT+9

By John Authers

John Authers is a senior editor for markets and Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A former chief markets commentator at the Financial Times, he is author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets.”

Legendary bond investor Bill Gross in 2011.

Photographer: Bloomberg

When the Credit Breaks

If something needs to break before the Federal Reserve relents and bond yields start to fall, what is it going to be? Back in March, it looked as though the backup in bond yields had broken something really important: the regional banking system. Several banks proved to have taken on too much interest-rate risk. Rescues, fire sales, and a Fed program to lend money to keep them liquid ensued.

Credit has continued to flow since then, however, and the corporate credit markets haven’t snapped yet. If that changes, it makes a recession far harder to avoid, and also sharply increases the risk of a major bankruptcy or failure of an institution to trigger a financial crisis. Credit matters. And it does look as though it’s beginning to budge.

The critical sign of something amiss comes from small caps. They are far more exposed to rising interest rates than larger companies, and the gulf in their performance has now grown quite dramatic. The Russell 2000 index of smaller companies has just dropped back below its level from the eve of the pandemic, essentially giving up all its gains since the dawn of the decade. Russell’s index of the top 50 stocks is still up almost 50% over that period:

There are many reasons for the large-caps’ outperformance, but credit is possibly the most important. When comparing when debt needs to be renewed for small and large caps in the US and Europe, the following chart from Societe Generale’s quantitative strategist Andrew Lapthorne shows that the US-based large caps of the S&P 500 seem to have locked in great deals. Everyone else faces a credit “wall” or “cliff”:

Small-caps’ share prices suggest credit is getting too tight, and the yields on their bonds are beginning to do the same. The spreads payable for taking on the extra risk of high-yield or “junk” bonds has remained very tight so far this year, fully repairing the damage from the March bank failures. Spreads are still not extreme by any measure; but they’re rising, and the trend seems to be clearly upward as the 200-day moving average has now been breached:

Small companies also face issues dealing with their bank managers, as well as with Mr. Market. The Federal Reserve’s survey of senior lending officers, which has been conducted quarterly since 1990, suggests that the proportion of banks tightening rather than loosening standards for commercial loans has now hit almost 50%. It’s only been exceeded during the worst moments of the pandemic, and the Global Financial Crisis:

A lot of smaller companies have another very serious problem when it comes to paying their debts: They don’t have any profits. This chart from Lapthorne shows that the proportion of “zombie” loss-making smaller companies is far higher in the US than Europe. This hasn’t mattered while rates have been low. Once higher rates are payable, it will — and might even contribute to a tip in the balance from the US to Europe:

Meanwhile, even the bigger companies of the S&P 500 are beginning to feel some pressure. Treasurers did a good job of locking in low rates when they were available in 2021, but they generally weren’t able to finance themselves for that long. Amounts due to be repaid increase noticeably next year, and then jump to levels that could be really problematic in 2025 and 2026, as illustrated in this chart of the S&P 500 (excluding financials) from Chris Senyek, chief investment strategist of Wolfe Research:

For a final sign of trouble in the offing, look to the consumer. Mahmood Noorani, the CEO of Quant Insight of London, shows that total interest payments by US consumers have surged of late as a share of wages and salaries. Again, this could easily contribute to a credit crunch:

Monetary policy generally works with an 18-month lag, Noorani points out — and it’s now been that long since the Fed started to hike. If credit is at last turning, it’s doing so on cue.

Gross Net Returns

On Monday, a bond market move was accelerated by an intervention from the legendary investor Bill Gross to say that he was now placing bets on short-term rates to fall. Points of Return commented that he left Pimco, which he founded, “after a big and unsuccessful bet that bond yields would rise after the financial crisis went bad.” While this was accurate as far as it goes, it’s been pointed out to me that it doesn’t tell the whole story. And indeed, the full story of Gross’s bad call back in early 2011 has very relevant lessons for us today.

The incident shows up clearly in the following chart, which compares the Pimco flagship Total Return’s performance to that of Bloomberg’s US Treasury index. Total Return’s long-term outperformance was remarkably consistent, with dramatic interruptions for the crises of 2000 and 2008. Then there was the much more self-imposed crisis for the fund in 2011, after it exited Treasuries altogether early in the year. Gross’s argument was that inflation was about to return after the flood of money that had been printed to tide through the GFC. In other words, he expected 2011 to pan out much as the last two years have done.

That October, Gross issued a now-famous “mea culpa” letter in which he described the year as a “stinker” and admitted his mistake. At that point, Total Return was in the bottom decile of all bond funds for 2011, after making its investors only 1.9% for the year. That incident shook Gross’s reputation for infallibility. But the way the fund rebounded once he’d admitted error was truly remarkable:

That mea culpa, and the mistakes that preceded it, were a big deal at the time, and earned Gross a lot of abuse. That was unfair. I was heading the Lex column of the Financial Times at the time and this was the final paragraph of the note I wrote:

"Mr Gross does not deserve abuse. Long-term investment managers can afford occasional mistakes. The question is their response. An investor’s key quality is emotional intelligence; the ability to make contrarian bets against the herd, and to admit a mistake, rather than hold on to a losing bet in the vain hope of eventually making back losses. Mr Gross has that quality. His investors, despite the lousy year he has given them, should be glad of it."

That judgment proves to have been pretty good. To err is human, and therefore inevitable. What makes a difference is to stay alive to the possibility that you are wrong, and be prepared to swallow the embarrassment and change course. By the time Gross left in 2014, the fund had made up all the ground lost during the “stinker” of 2011.

The bond market is going to inflict a stinker on many people in the months ahead. Accept that. The key will be how to deal with it when it happens.

Mr. Xi Visits the Bank

There’s big news out of China. President Xi Jinping has paid a personal visit to the team at the People’s Bank of China, for the first time in the decade he has been leading the country. He’s also ramping up his support for the economy by issuing additional sovereign debt and raising the budget deficit ratio. All of this is unusual. China tends to keep to its plans, and has rarely adjusted the budget mid-year.

As Bloomberg has reported, the legislature approved a rise in the fiscal deficit ratio for this year to about 3.8% of gross domestic product. This is well above the 3% set in March, which the government has generally considered a limit. This will involve issuing additional sovereign debt worth 1 trillion yuan ($137 billion) that is designed to help local authorities offload more problematic loans.

The budget revision highlighted concerns among top leadership about the outlook for 2024, and how it compares to the US. Third-quarter GDP has come in above expectations — and is on track to hit Beijing’s 5% growth target for the year. Plainly, the government’s focus is now fully on shoring up the economy and financial markets amid a deepening property crisis and deflationary pressures.

For the rest of the world, the big question is whether it’s good news that the authorities are acting, or bad news that they think they need to.

Mark Williams of Capital Economics expected the move. “Fiscal policy has been a prop to growth in China over the last few quarters. These new steps will keep it supportive but not deliver any additional boost,” he said. The mid-year revision signals “clear concern” about near-term growth. If anything, he questions why the injection isn’t “any bigger.”

While some have interpreted that half of the extra funds will be used this year, Bloomberg Economics’ David Qu believes that any construction activity will “mainly land in 2024” thanks to the time needed to raise and allocate funds. This is BE’s model:

More news came out of the legislature Tuesday, including the ouster of the defense minister and the removal of a former foreign minister from his remaining role as State Councillor. In what was a widely expected move, the Standing Committee named Lan Fo’an as finance minister to replace Liu Kun.

Xi also dropped by the State Administration of Foreign Exchange in Beijing. The symbolic visit comes amid his desire to better understand China’s $3 trillion of currency reserves, according to Bloomberg’s reporting. It could show he grasps the need to assuage investor concern amid high-profile reshuffles, or alternatively that he wants to demonstrate “centralized and unified” leadership over the financial industry.

But it’s not a good sign, according to Christopher Low of FHN Financial. “China has an enormous debt burden and wants to stimulate growth. When leaders start eyeing foreign reserves as a source of spending, it generally ends badly, as central bankers from Argentina and Brazil can attest,” Low wrote. “In the past decade, China has gone from more than adequate reserves to maybe enough to protect its currency.”

For investors, the most direct implications may be for Chinese stocks, which are now at their lowest levels since 2019. The Clocktower team in Shanghai said that investors are mainly concerned about two things: the risk of further credit deceleration that will likely translate into lower GDP given Beijing’s failure to rejuvenate the property market, and corporate earnings growth.

“What explains the divergence between Beijing’s confidence in the economy and the widespread pessimism in the market?” Clocktower asked. “The reason, we believe, is that policymakers are backward looking and solely focus on achieving a near-term growth target of around 5%. In contrast, investors are forward-looking, believing that the lack of stimulus efforts today would lead to a much lower growth tomorrow, from 2024 and onwards.”

—Isabelle Lee

Earnings Recap

A quick tour of earnings after market hours Tuesday. As Points of Return wrote, big tech companies are projected to jump 34% from a year earlier on average, according to analyst estimates compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence. But it’s easy to forget that the biggest have to compete with each other. There was a harsh reminder of that:

Alphabet

Shares of Alphabet Inc. fell almost 7% in late trading after the company reported that revenue and profit from its cloud business had missed estimates. This raised concerns about future growth, especially since the cloud unit — the third-largest player in the market, after Amazon.com Inc. and Microsoft Corp. — was expected to take the lead on growth. The unit reported operating income of $266 million, far below estimates of $434 million. Overall, the report was healthy, with net income comfortably ahead of estimates. That wasn’t what mattered.

Microsoft

In a mirror image of Alphabet, Microsoft enjoyed stronger-than-expected first-quarter sales, bolstered by recovering cloud-computing growth. Shares rose almost 5% in late trading. Azure cloud-services sales gained 29% compared with 26% growth in the previous quarter. Revenue rose 13% to $56.5 billion, topping analysts’ average projections, while profit was $2.99 a share.

The market reaction was to make what looked like a direct switch out of Alphabet and into Microsoft:

Some of the Magnificent Seven’s growth will have to come at the expense of other members. Best to factor that in.

— Isabelle Lee