블룸버그 기사 요약

’Tis the Season…

주요 금융기관들의 2024년 전망이 벌써 나오고 있음

지금부터 내년 사이에 의외의 역사적 사건이 발생하면 이런 전망은 틀릴 수 있음

하지만 장기 전망에서 나오는 아이디어는, 만약 그것이 맞다면, 시장을 이기고 돈을 벌 수 있는 방법이 될 것

이러한 장기적인 관점에서, 화요일에 발표될 10월 소비자 물가 지수에 대해 살펴보겠음

Wait and CPI

채권 시장이 혼란한 상황에서, 인플레이션 수치는 채권 수익률에 큰 영향을 줄 수 있음

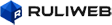

그러나 블룸버그 이코노미스트들은 10월 CPI에 대해 대부분 비슷한 전망을 내놓고 있음

문제는 전년 대비 근원 CPI가 하락하지 않을 것이라는 점 (4.1%)

이는 1년만에 처음 있는 일이며, 연준이 안심할 수 없을 정도로 높은 수준임

근원 CPI가 4%를 밑돌면, 국채 수익률은 하락하고, 주식은 연말까지 상승할 동력을 얻게 될 것

하지만 이는 내년 주가 지수 전망에는 부정적인 소식이 될 것

근원 CPI가 예상보다 훨씬 높게 나오면, 이는 시장에 혼란을 초래할 것

시장이 이런 상황을 가격에 반영하지 않았기 때문

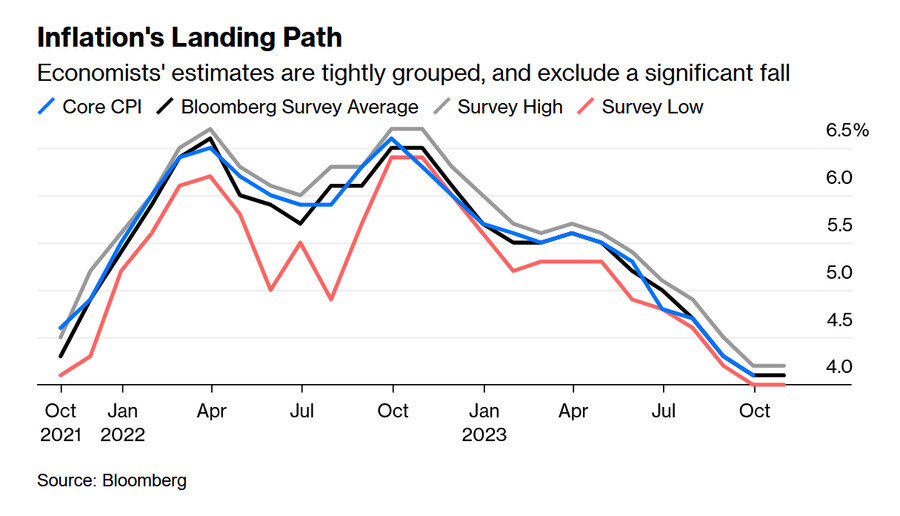

9월 슈퍼코어 인플레이션(근원 서비스 인플레이션 - 주거비)이 올해 들어 가장 높았던 것도 걱정스러움

슈퍼코어 인플레이션은 주로 임금의 영향을 받기 때문에, 연준이 주목하는 지표임

만약 10월에도 슈퍼코어 인플레이션이 높게 나온다면, 기준 금리 인상은 끝났다는 믿음이 흔들릴 것

그리고 전월 대비 근원 CPI가 8월, 9월에 이어 10월에도 오른다면 이것도 걱정거리가 될 것

연준 인사들의 상당수가 기대 인플레이션을 중요하게 생각함

11월 미시간대 장기 기대인플레이션이 3.2%로 집계됐음

이는 연준의 목표치인 3%보다 높으며, 2011년 이후 가장 높은 수준임

채권시장에서 가장 선호하는 장기 기대인플레이션 지표 가운데 하나인 '5년후 5년 포워드 기대인플레이션율'(5-year, 5-year forward breakeven inflation rate)도 지난 몇 년 간 3% 아래에 머물렀지만, 최근 몇 달 동안 눈에 띄게 올랐음

How High Are Rates Really?

세계 각국의 실질 금리 격차가 커진 상황

실질 금리가 마이너스인 국가들이 아직도 있으며, 반대로 실질 금리가 매우 높은 국가들은 멕시코, 브라질, 러시아 등이라는 건 놀라운 일

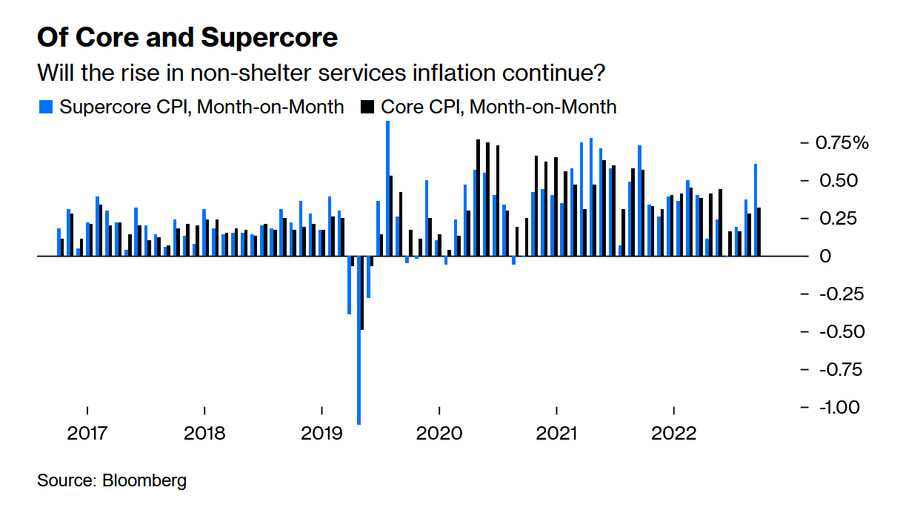

선행적 실질 금리(인플레이션 예상치를 이용)와 후행적 실질 금리(실제 인플레이션 수치를 이용)의 격차는 기준 금리 인상기에 커짐

그래서 현재의 실질 금리가 충분히 제약적인지는 사후적으로 알 수 있을 것

달리 말하면, 인플레이션 전망은 아직도 불투명하다는 의미

Hard Labor

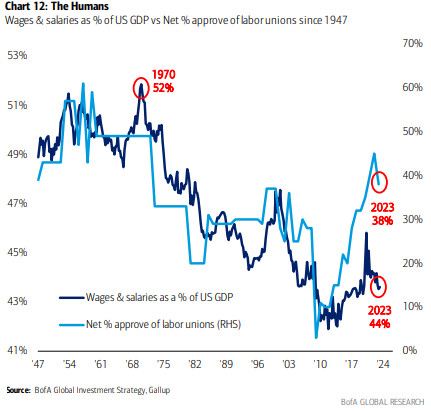

BofA의 마이클 하넷에 따르면, GDP에서 임금이 차지하는 비중은 앞으로 더 오를 것

노조에 대한 미국인들의 지지율은 50년만에 가장 높은 수준이지만, GDP 대비 임금의 비율은 여전히 낮기 때문

이로 인해 높은 인플레이션이 지속되겠지만, 사회적 불평등은 개선될 것

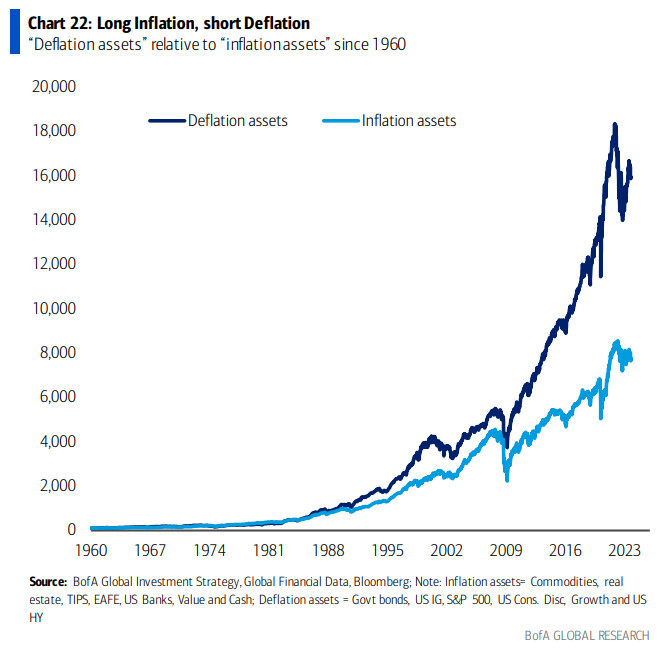

마이클 하넷에 따르면, 인플레이션 시대에는 실물 자산에 투자해야 함

→ 상품, 부동산, 물가 연동 채권, 미국 은행, 가치주, 현금 등

금융 자산 대비 실물 자산의 가격은 1925년 이래 가장 낮은 수준

1990년대 후반에 금융 자산 대비 실물 자산 가격이 반등했으나 2008년 금융위기 이후 급락했음

실물 자산은 희소하고, (금융 자산에 비해) 싸고, 투자자가 적으며, 인플레이션을 헷지할 수 있고, 포트폴리오를 다각화할 수 있음

1950년대 이후 모든 실물 자산 가격은 인플레이션과 양의 상관관계를 보였음

특히 다이아몬드, 미국 농장, 금은 미국 소비자 물가 지수와 상관관계가 가장 높음

Contrarian Forecasts

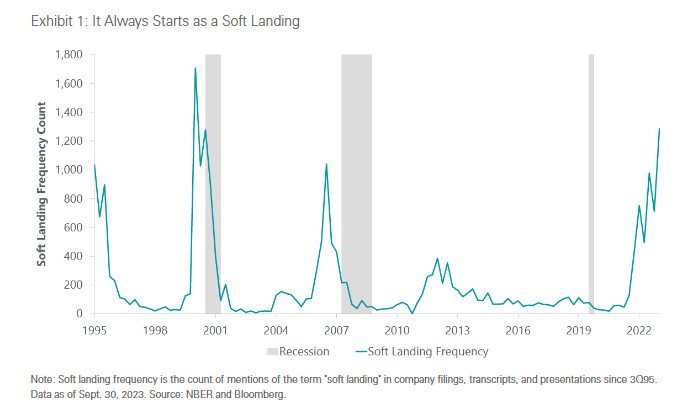

1) 최근 연착륙 전망이 힘을 얻고 있음

연착륙/경착륙 같은 비유적인 표현이 비교적 최근에 쓰이기 시작했음

1995년 이후 기업들의 연착륙에 대한 언급이 급증하면, 결국 경기침체가 발생했음 (닷컴 버블, 2008년 금융위기)

그리고 지금도 기업들이 연착륙을 자주 언급하고 있음

이번에는 경기 침체를 피할 수 있다면 놀라운 일이 될 것

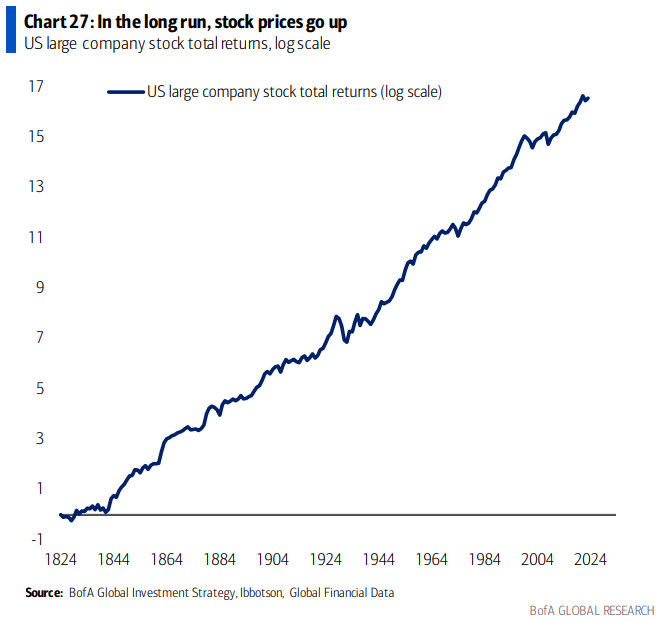

2) 주식, 특히 대형 기술주가 어려움을 겪을 것이라는 전망이 늘어나고 있음

하지만 장기적으로 보면, 주가는 결국 올랐음

물론 단기적으로 주가는 내릴 수 있고, 포트폴리오를 다각화하려면 주식 이외의 자산에도 투자해야 함

하지만 주가는 대부분의 시간 동안 올랐기 때문에, 주식에서 아예 발을 빼는 것은 위험함

==============================================

The fog of the war on inflation hasn’t yet cleared. When it does, you might see something out of the beginning of Ronald Reagan’s presidency.

2023년 11월 13일 오후 2:01 GMT+9

By John Authers

John Authers is a senior editor for markets and Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A former chief markets commentator at the Financial Times, he is author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets.”

Organized labor could well attain its strongest p-osition in four decades.

Photographer: Frederic J. Brown/AFP/Getty

’Tis the Season…

So we’re not even halfway through November, and already the Christmas decorations are going up. It seems to happen earlier every year. The same is true of the season for major investment groups to publish massive outlook documents, crammed with research and predictions for the year ahead, even with six or seven weeks of 2023 to go.

At one level, this is silly. Viewing the world in calendar years can distort perception, and publishing this early means running massive event risk. My favorite example of that genre was the Economist’s “World in 1990” publication, which appeared in November. With reform sweeping the communist bloc, it rated that chances of change in what was still Czechoslovakia at 0 out of 10, and in Romania at -10 out of 10. Before 1990 had even started, the Velvet Revolution had swept the communists from power in Prague, while Romanian strongman Nicolae Ceausescu had been lined up against a wall and shot.

In the more mundane world of markets, there are well-known phenomena that cause prices to move as the year ends. Portfolio managers resort to “window dressing,” buying stocks that have been doing well to make their holdings look good. The need to manage capital gains taxes drives sales to maximize paper losses or limit gains. Some people dive to put money to work to take advantage of tax relief.

So, the whole exercise is a tad silly. However, like Christmas, it’s a seasonal ritual that serves a purpose. It’s good for analysts and researchers to escape the short-termism of weekly notes, step back, try to see a bigger picture, and work out dispassionately what their assumptions imply for the future. And a lot of the time, the year-ahead exercise allows them to publish niggling ideas that never quite find their way into the weekly download. Such ideas, if they’re right, are exactly the way to make money and beat the market.

So, in this spirit, here is a Points of Return look forward to the next main event for world markets, Tuesday’s publication of US consumer price inflation for October, in the context provided by the long-term outlook notes received so far.

Wait and CPI

When bonds have been so turbulent, there is always a chance that inflation numbers could cause a big move in one direction or another. But Bloomberg’s survey of economists’ predictions suggest that there is more consensus over the October numbers than there has been since the inflation survey got under way in earnest two years ago. All the estimates for core CPI (excluding food and fuel) are tightly bunched around an average that is exactly in line with the previous month. The good news is that economists are confident they have a handle on inflation now. The bad news is that they are not expecting the year-on-year rate to decline. If that turns out to be true, it would be the first time in a year that core CPI hasn’t fallen, at a level that remains too high for the Federal Reserve’s comfort:

In such circumstances, it doesn’t take much to move the market needle. If core does drop below 4%, we can expect another relief fall in bond yields, and more oomph for an end-of-year rally in stocks (which will automatically make predictions that have already been published for the S&P at the end of next year look more pessimistic). A significant rise would come as a big surprise, and it would create a mess — but that’s in large part because it seems very unlikely.

The critical component of inflation that will grab attention, and could create a reaction even if the overall numbers are in line with expectations, is the Fed’s favored “supercore” measure, its label for services inflation excluding shelter costs. This is a growing part of our expenditures, and it is particularly dependent on labor costs, which are a big part of service companies’ budgets.

There are good arguments about whether supercore should matter that much to the central bank, but it appears to be a fact that it does. Thus the fact that it jumped to its highest monthly increase of 2023 in September caused concern among investors. If October’s number confirms that it wasn’t a fluke, then that could do considerable damage to confidence that rate hikes are over, and certainly the belief that cuts will come soon. Also, the month-on-month rise in core CPI rose in both August and September; it would be an unpleasant surprise if that were to happen again.

As for the underlying drivers of inflation, there’s an ongoing debate over whether expectations are central to pushing prices higher, by changing companies’ and consumers’ behavior, or incidental. There are plenty at the Fed who think they matter. The New York Fed’s own measure of consumer forecasts is due Monday, but the University of Michigan’s regular survey suggested a worrying development, with expectations for the period from five to 10 years from now reaching 3.2%. That’s above the Fed upper limit of 3%, and it’s the highest since the oil spike that preceded the Global Financial Crisis in the summer of 2008:

The chart also shows the bond market’s version of the same forecast, known as the five year-five year breakeven. This has been relatively calm throughout the last few years, and it remains below 3% — but again, it’s tended to shift upward noticeably in the last few months.

How High Are Rates Really?

Broadening focus now, the global monetary authorities are still widely dispersed in the action they’ve taken. The following chart, from HSBC, shows a crude measure of real rates for each country, by subtracting the headline inflation rate from the official target policy. It’s startling how many still have negative real rates, and that the greatest rigor has been shown by Mexico, Brazil and Russia, none of them thought of as founts of monetary orthodoxy:

Is this the best way to measure real interest rates? Probably not. But it’s hard to find anything clearly better. In Morgan Stanley’s economic outlook for 2024, penned by Seth Carpenter and his team, we get a track of the fed funds rate after substituting the breakeven rate, and Michigan survey rates that were prevalent at the time, as well as an “ex post” measure that subtracts actual inflation. They’re all over the place, particularly so during the difficult months when the Fed was steadily raising rates:

If there is uncertainty about such basic building blocks of monetary policy, that’s because inflation hits different people differently. Carpenter says:

"Although central banks refer to real interest rates all the time, the ability to measure real rates is limited and subject to uncertainty measured in percentage points [not basis points]. Consequently, policy will always have a backward-looking, data-dependent component as the effect of the stance of policy on the real economy is revealed over time."

Or in other words, don’t take anything for granted. The fog of the war on inflation hasn’t cleared.

Hard Labor

Then there is the issue of labor, for which a wide focus is very useful. Michael Hartnett of Bank of America Corp. has just published his annual “The Longest Pictures” chartbook, which aims to get us ready for 2024 by looking at current trends through a very long focus. And one key point is that the balance between labor and capital looks as though it’s turning, even though public support for unions in the US, and the share that wages take of the economy, have dipped back again since the pandemic shutdowns pushed them higher.

As it stands, unions are about as popular as they’ve been at any time in 50 years, and yet wages remain a lower share of the economy than they were then. It’s probably wise to assume that this number will increase (meaning more social harmony, though after industrial disruptions have run their course, but also more inflation):

With Hollywood actors the latest union to win a big victory over employers, it looks reasonable to expect labor to continue gaining strength. If it doesn’t get back to the power enjoyed in 1970, organized labor might still be able to scramble back to the kind of influence it had at the outset of Ronald Reagan’s presidency. That would certainly imply a need to get used to higher typical inflation rates, ideally with falling inequality.

Hartnett goes from this to suggest that the big trade is to buy what he calls “inflation assets,” while getting out of assets that benefit from deflation. The latter have had things all their own way with few interruptions since the early 1980s. Now, he says, it’s time for: commodities, real estate, inflation-linked bonds, US banks, value stocks, and cash:

He is not, presumably, suggesting that this will happen in a straight line, because markets and economies don’t work like that. But it seems a robust assumption. It gets further backing from the following piece of financial archaeology, which compares real assets to financial assets going back to 1925. Real assets are enjoying the beginning of a rally after falling to their worst relative low since the series started. There was another similar rise for real assets that started in the late 1990s, but it was snuffed out by the GFC:

If you think that a suggestive chart isn’t quite sufficient basis to bet on an economic sea change, BofA offers the following rationale:

"Real assets are scarce, cheap (relative to financial assets close to 100-year lows), under-owned, a hedge against inflation, and diversify portfolios. All individual real assets are positively correlated with inflation since 1950… diamonds, US farmland and gold have the highest correlation between change in the price and the US CPI inflation rate"

That argument should stay intact whatever we learn about US inflation on Tuesday.

Contrarian Forecasts

Two brief points to emerge. First, there’s quite a consensus that the US will manage to execute an economic “soft landing,” or in other words avoid a recession. The history on the aviation analogy doesn’t go back all that far, but the following beautiful piece of data-mining by Jeffrey Schulze, strategist at ClearBridge Investments, suggests that we shouldn’t find this too comforting.

Digging through company documents and filings going back to 1995, we find that mentions of a soft landing have spiked like this twice before — and on both occasions were followed by a recession. Covid might have scrambled perceptions, as this was one of the very rare examples of a true external shock forcing the world into recession almost instantaneously. Usually, recessions come on more gradually than that, and appear to be on course for a soft landing before hitting the ground hard:

If we get away without a recession, it’s going to be quite something. Meanwhile, it’s also a popular call that stocks, particularly the “Magnificent Seven” internet platforms that are dominating returns, will have a tough time. That’s reasonable, and stocks can go downward or sideways for a long time. In the very long term, they go up. This is how US large-cap stocks have performed over the last 200 years, on a log scale:

It’s too lazy just to rely on the long run to bail you out, and there is a need to look beyond stocks. But the weight of history does show that it’s very risky indeed to be out of stocks altogether. I often wonder whether we should have a health warning at the end of each newsletter. WARNING: YOU SHOULD BE IN THE STOCK MARKET MOST OF THE TIME; IT’S RISKY TO BE OUT OF IT.