한국의 장난감 매장에서 한 여성과 아이가 봉제인형을 보고 있다.

Photographer: SeongJoon Cho/Bloomberg

한국 인구가 2060년대 말까지 3500만까지 급락하고, 이로인해 한국사회가 극도의 위기에 빠져들 것이란 경고가 나왔다. 극도로 낮은 출산율로 인해 흑사병이 창궐한 14세기 유럽보다 한국의 인구가 빠르게 급감할 것이라면서다.

2일(현지시간) 뉴욕타임스(NYT) 칼럼니스트 로스 다우서트는 ‘한국은 사라지고 있나’라는 제목의 칼럼을 통해 이같이 주장했다.

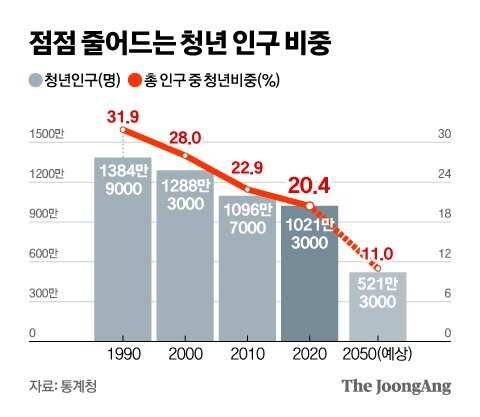

그는 거의 모든 선진국의 경우 출산율이 하락해도 미국(1.7명), 프랑스(1.8명), 이탈리아(1.3명)와 같이 합계 출산율 1.5명 수준에서 머무르는 것과 달리 한국의 경우 2018년 1.0명이 깨진 이후 현재 0.7명을 기록하고 있다고 알렸다. 통계청은 지난달 29일 3분기 합계 출산율이 0.7명으로 1년 전보다 0.1명 줄었다고 발표했다.

다우서트는 “이는 한 세대만 지나도 200명이 70명으로 줄어드는 것으로, 14세기 흑사병으로 인한 인구 감소를 넘어선다”며 “한 세대가 더 지나면 200명이 25명 이하가 된다. 스티븐 킹 소설 ‘스탠드’에서 나오는 가상의 슈퍼독감으로 인한 급속한 인구 붕괴 수준이 된다”고 지적했다. 정확한 통계는 없지만, 14세기 유럽 인구의 30~50% 정도가 흑사병으로 사망했을 것이라 추정한다.

그는 이 같은 극단적 인구 감소가 지속될 것이라고 보지는 않았다. 그럼에도 오는 2067년까지 한국의 인구가 3500만명 이하로 떨어질 수 있다는 한국 통계청의 인구추계(저위 추계 시나리오 기준)를 인용해 “한국을 위기로 몰아넣기 충분한 수준”이라고 전했다.

한국이 가파른 인구 절벽으로 인해 불안한 미래를 맞을 것이라고 다우서트는 내다봤다. 한국사회가 심각한 경제적 쇠퇴를 겪고, 현재 서유럽 지역 등에서 사회 불안정 요소로 꼽히는 이민자를 대거 수용할 수밖에 없다는 전망이다. 구체적으로는 인구 구조가 ‘역피라미드’ 형태로 바뀌면서 노인은 유기되고, 유령도시 현상이 나타나고, 젊은 세대는 해외 이민을 떠날 것이라고 우려했다. 그는 또 “현재 합계 출산율 1.8명인 북한이 어느 시점에서 남침을 선택할 수도 있다”고 경고했다.

다우서트는 한국이 예외적으로 낮은 출산율을 기록하게 된 과정도 분석했다. 다우서트에 따르면 한국인은 성장, 연애, 출산 과정 모두에서 출산율 증가에 반하는 현상들이 나타나고 있다.

그는 한국의 잔혹한 입시경쟁 문화는 부모의 걱정과 자녀의 고통을 부르며 가족생활 자체가 결과적으론 ‘지옥 같은’ 것으로 인식됐다고 했다.

또 페미니스트와 반페미니스트의 극심한 대립이 남녀 갈등을 만들어 결혼율을 사상 최저 수준으로 떨어뜨렸고, 보수적인 사회 분위기로 혼외 출산율도 낮다고 전했다. 인터넷 게임 문화 등이 한국 젊은 남성을 이성보다 가상의 존재에 빠져들게 한 게 혼인율 하락으로 이어졌을 수 있다고 다우서트는 언급했다.

다우서트는 “이런 현상은 미국도 경험하고 있는 현상이 더 뚜렷하게 나타나는 것으로, 한국의 상황은 단순히 놀라운 현상이 아닌 미국에 일어날 수 있는 일에 대한 경고”라고 했다.

==================================

(NYT) Is South Korea Disappearing?

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/02/opinion/south-korea-birth-dearth.html

By Ross Douthat

Opinion Columnist

Dec. 2, 2023, 7:00 a.m. ET

For some time now, South Korea has been a striking case study in the depopulation problem that hangs over the developed world. Almost all rich countries have seen their birthrates settle below replacement level, but usually that means somewhere in the neighborhood of 1.5 children per woman. For instance in 2021 the United States stood at 1.7, France at 1.8, Italy at 1.3 and Canada at 1.4.

But South Korea is distinctive in that it slipped into below-replacement territory in the 1980s but lately has been falling even more — dropping below one child per woman in 2018, to 0.8 after the pandemic, and now, in provisional data for both the second and third quarters of 2023, to just 0.7 births per woman.

It’s worth unpacking what that means. A country that sustained a birthrate at that level would have, for every 200 people in one generation, 70 people in the next one, a depopulation exceeding what the Black Death delivered to Europe in the 14th century. Run the experiment through a second generational turnover, and your original 200-person population falls below 25. Run it again, and you’re nearing the kind of population crash caused by the fictional superflu in Stephen King’s “The Stand.”

By the standards of newspaper columnists I am a low-birthrate alarmist, but in some ways I consider myself an optimist. Just as the overpopulation panic of the 1960s and 1970s mistakenly assumed that trends would simply continue upward without adaptation, I suspect a deep pessimism about the downward trajectory of birthrates — the kind that imagines a 22nd-century America dominated by the Amish, say — underrates human adaptability, the extent to which populations that flourish amid population decline will model a higher-fertility future and attract converts over time.

In that spirit of optimism, I don’t actually think the South Korean birthrate will stay this low for decades, or that its population will drop from today’s roughly 51 million to the single-digit millions that my thought experiment suggests.

But I do believe the estimates that project a plunge to fewer than 35 million people by the late 2060s — and that decline alone may be enough to thrust Korean society into crisis.

There will be a choice between accepting steep economic decline as the age pyramid rapidly inverts, or trying to welcome immigrants on a scale far beyond the numbers that are already destabilizing Western Europe. There will be inevitable abandonment of the elderly, vast ghost towns and ruined high rises, and emigration by young people who see no future as custodians of a retirement community. And at some point there will quite possibly be an invasion from North Korea (current fertility rate: 1.8), if its southern neighbor struggles to keep a capable army in the field.

For the rest of the world, meanwhile, the South Korean example demonstrates that the birth dearth can get much worse much faster than the general trend in rich countries so far.

This is not to say that it will, since there are a number of patterns that set South Korea apart. For instance, one oft-cited driver of the Korean birth dearth is a uniquely brutal culture of academic competition, piling “cram schools” on top of normal education, driving parental anxiety and student misery, and making family life potentially hellish in ways that discourage people from even making the attempt.

Another is the distinctive interaction between the country’s cultural conservatism and social and economic modernization. For a long time the sexual revolution in South Korea was partially blunted by traditional social mores(=conventions) — the nation has very low rates of out-of-wedlock births (혼외 출산), for instance. But eventually this produced intertwining rebellions, a feminist revolt against conservative social expectations and a male anti-feminist reaction, driving a stark polarization between the sexes that’s reshaped the country’s politics even as it’s knocked the marriage rate to record lows.

Bae In-kyu, the head of Man on Solidarity, one of South Korea’s most active anti-feminist groups, led a rally in Seoul in December 2021. He has stated, 'Feminists are a social evil,' as reported by Woohae Cho for The New York Times.

It also doesn’t help that South Korea’s conservatism is historically more Confucian and familial than religious in the Western sense; my sense is that strong religious belief is a better spur to family formation than traditionalist custom. Or that the country has long been out on the bleeding edge of internet gaming culture, drawing young men especially deeper into virtual existence and further from the opposite sex.

But now that I’ve written these de/s!crip/ions, they don’t read as simple contrasts with American culture, so much as exaggerations of the trends we’re experiencing as well. (Not A so much as B)

We too have an exhausting meritocracy. We too have a growing ideological division between men and women in Generation Z. We too are secularizing and forging a cultural conservatism that’s anti-liberal but not necessarily pious, a spiritual-but-not-religious right. We too are struggling to master the temptations and pathologies of virtual existence.

So the current trend in South Korea is more than just a grim surprise. It’s a warning about what’s possible for us.